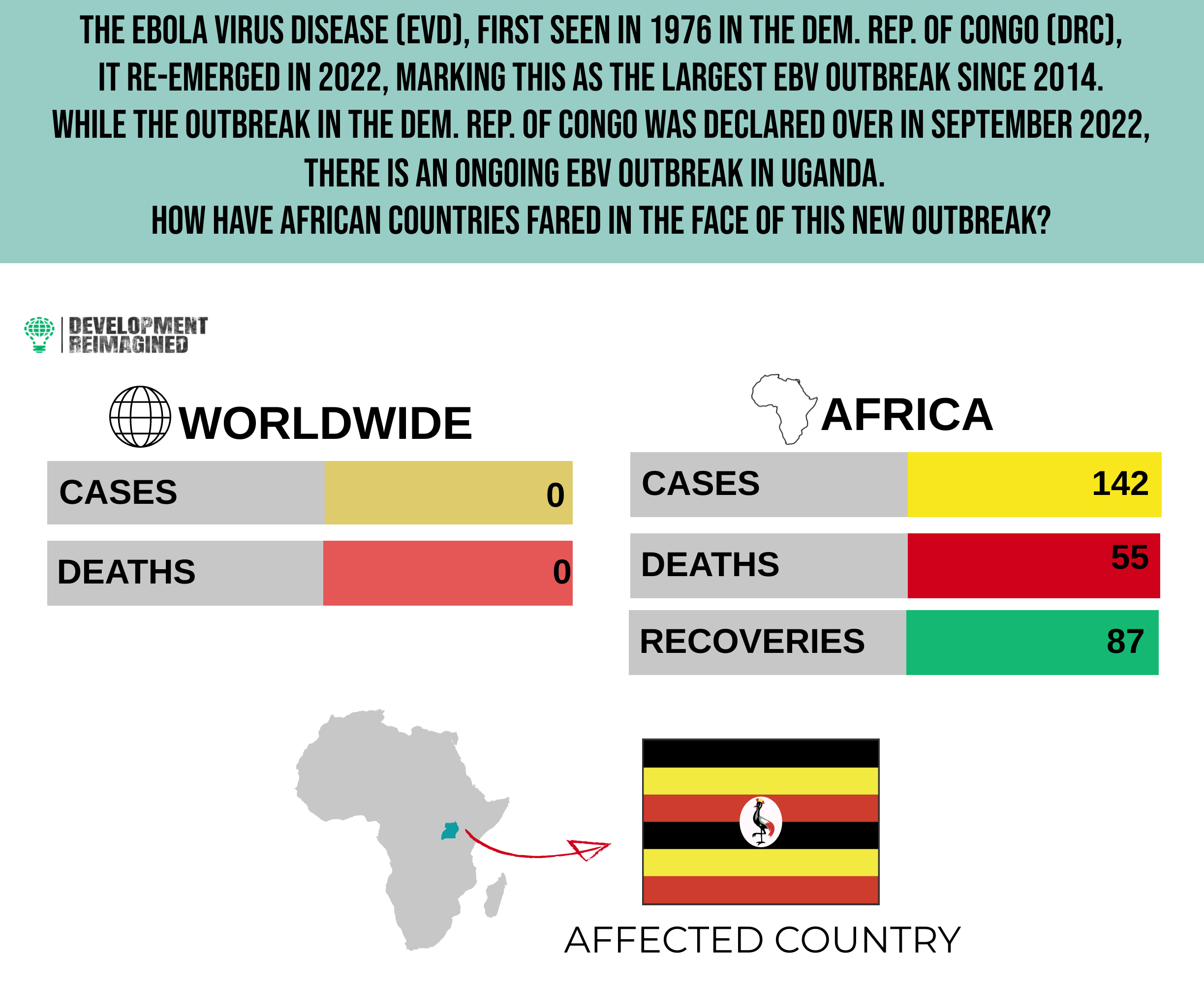

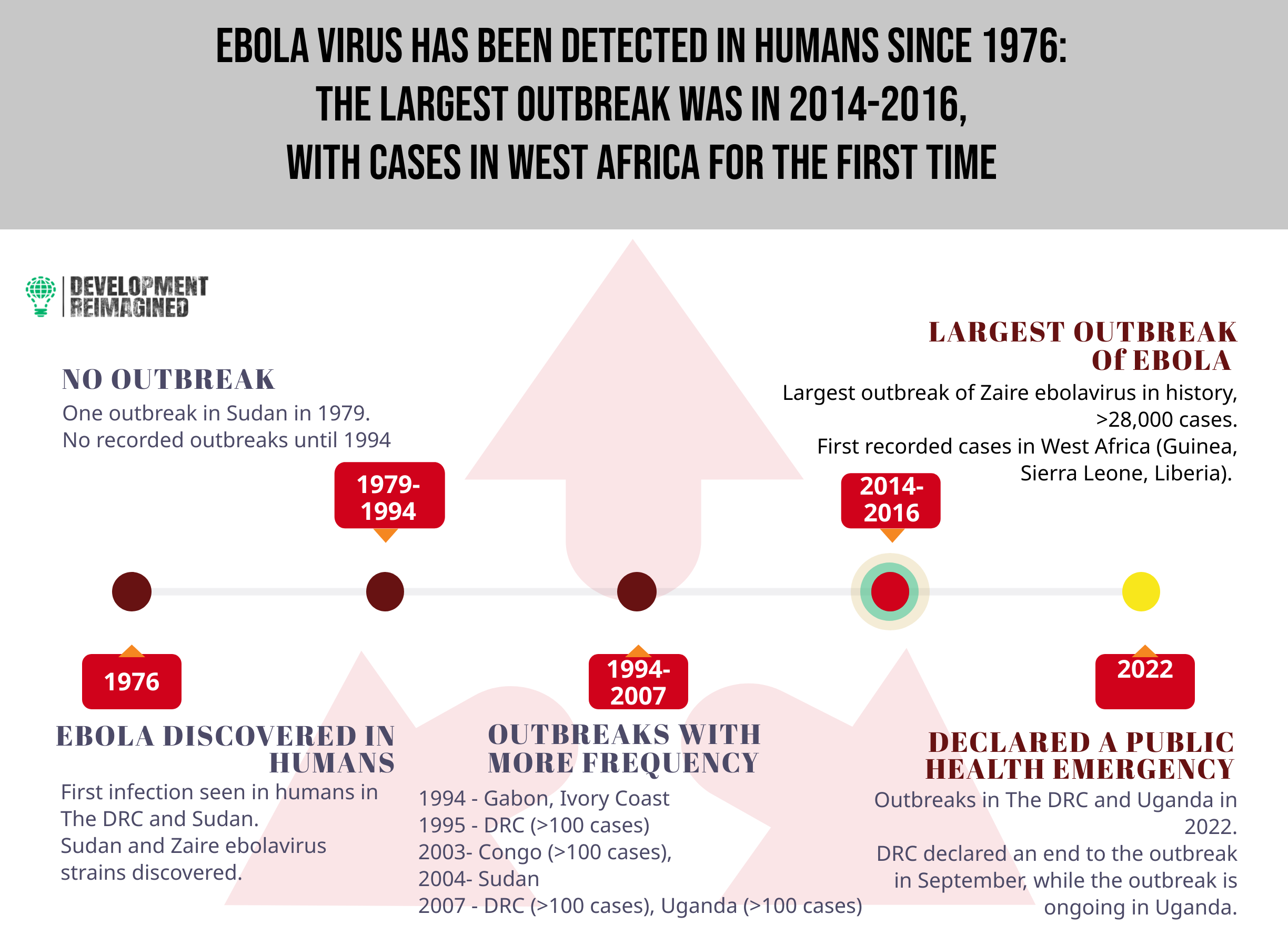

Nearly ten years after the Sudan Ebola virus (SUDV) was first discovered in Uganda in 2012, the deadly Ebola virus disease (EVD), also known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, has resurfaced in a new outbreak.

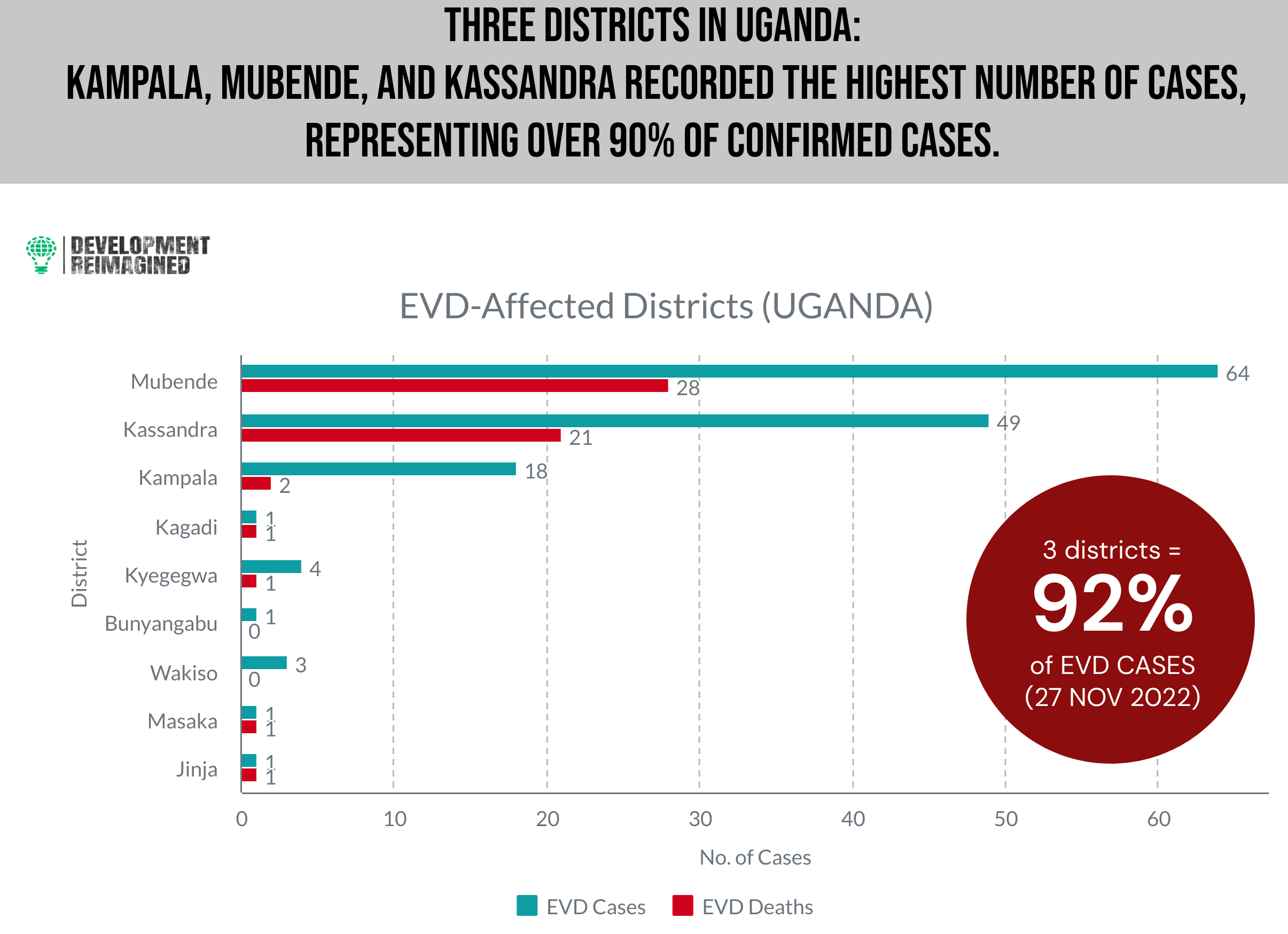

Following the confirmation of the first of over 55 fatalities, the World Health Organization’s Regional Office for Africa (WHO-AFRO) and the Ugandan Ministry of Health jointly declared an EVD outbreak in the Mubende District of Central Uganda on September 20, 2022.

How has Uganda fared with its management?

Nigeria in 2014 proved that successful Ebola containment can be achieved with limited resources, via careful collaboration between the private sector, resilient healthcare workers and the international community.

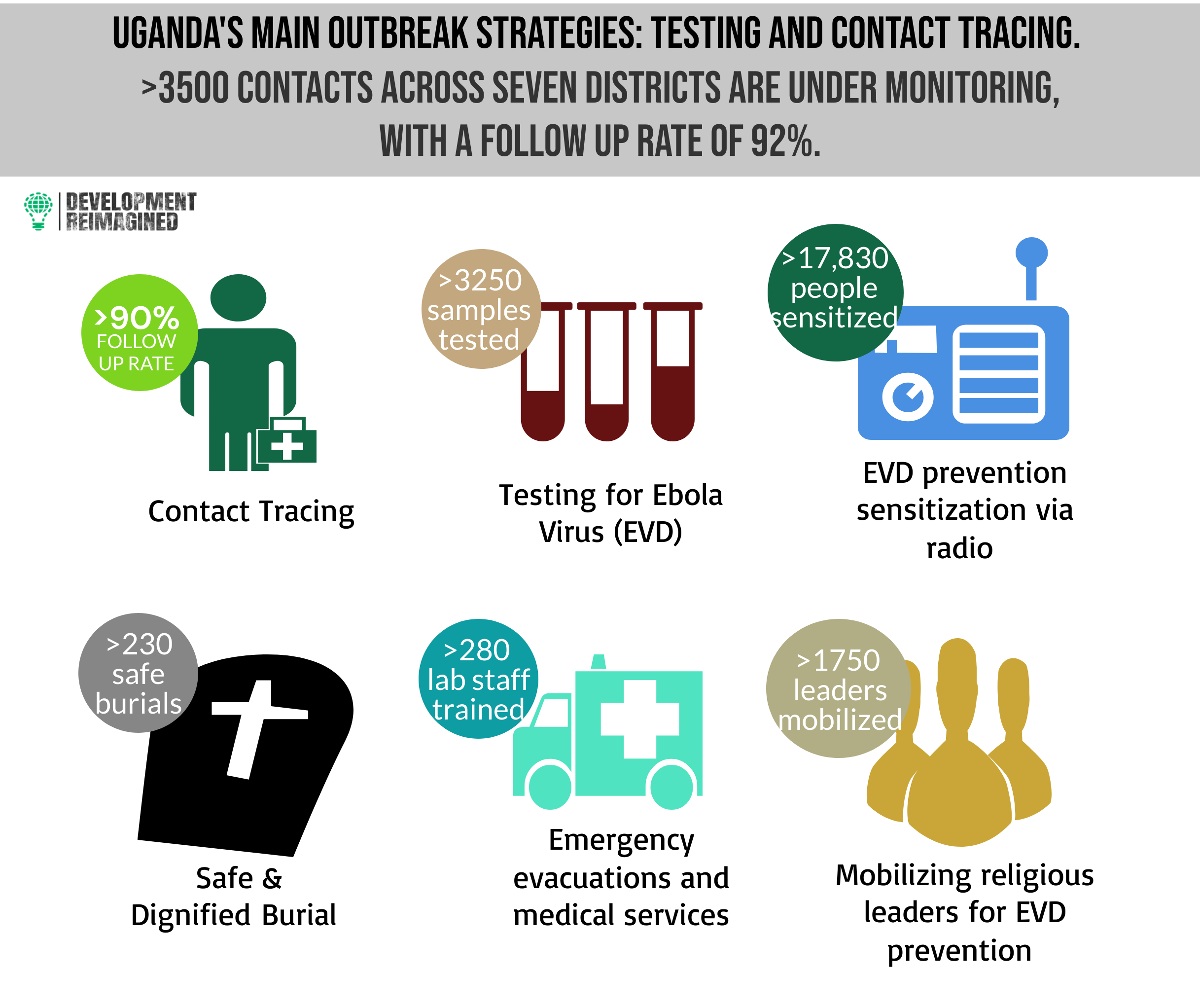

Following the 1st confirmed case, the Ugandan President announced a 21-day lockdown from 15 October in the districts of Mubende and Kassanda to contain the EVD outbreak. Other temporary measures employed were an overnight curfew, the closure of places of worship and entertainment, and restrictions on travel in and out of the affected districts. Additional measures involved sensitization campaigns via media and religious influence, as well as the enforcement of safe burial practices. The most pressing concern for this outbreak is that it is caused by the Sudan strain of Ebola, for which there is no approved vaccine, unlike the more common Zaire strain.

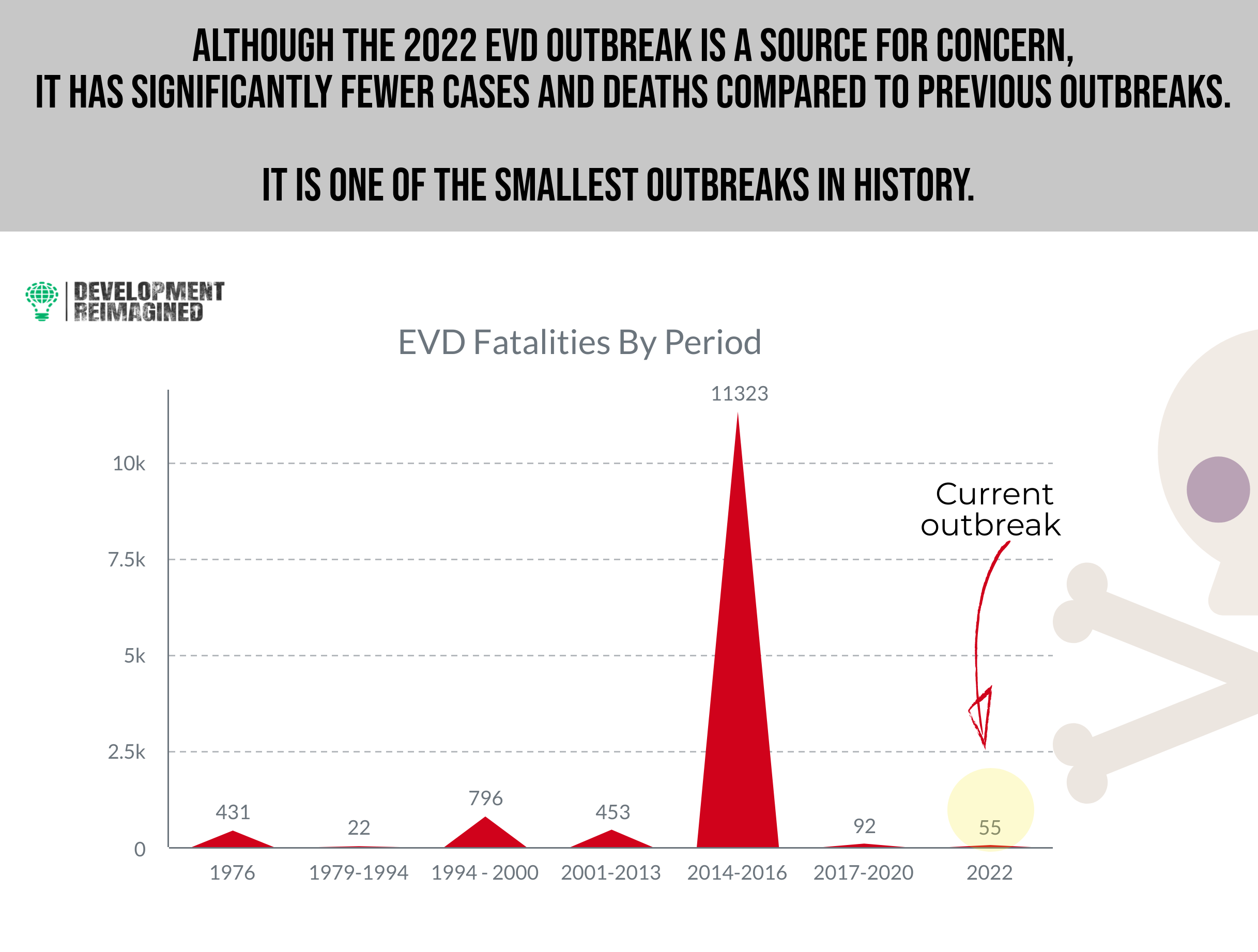

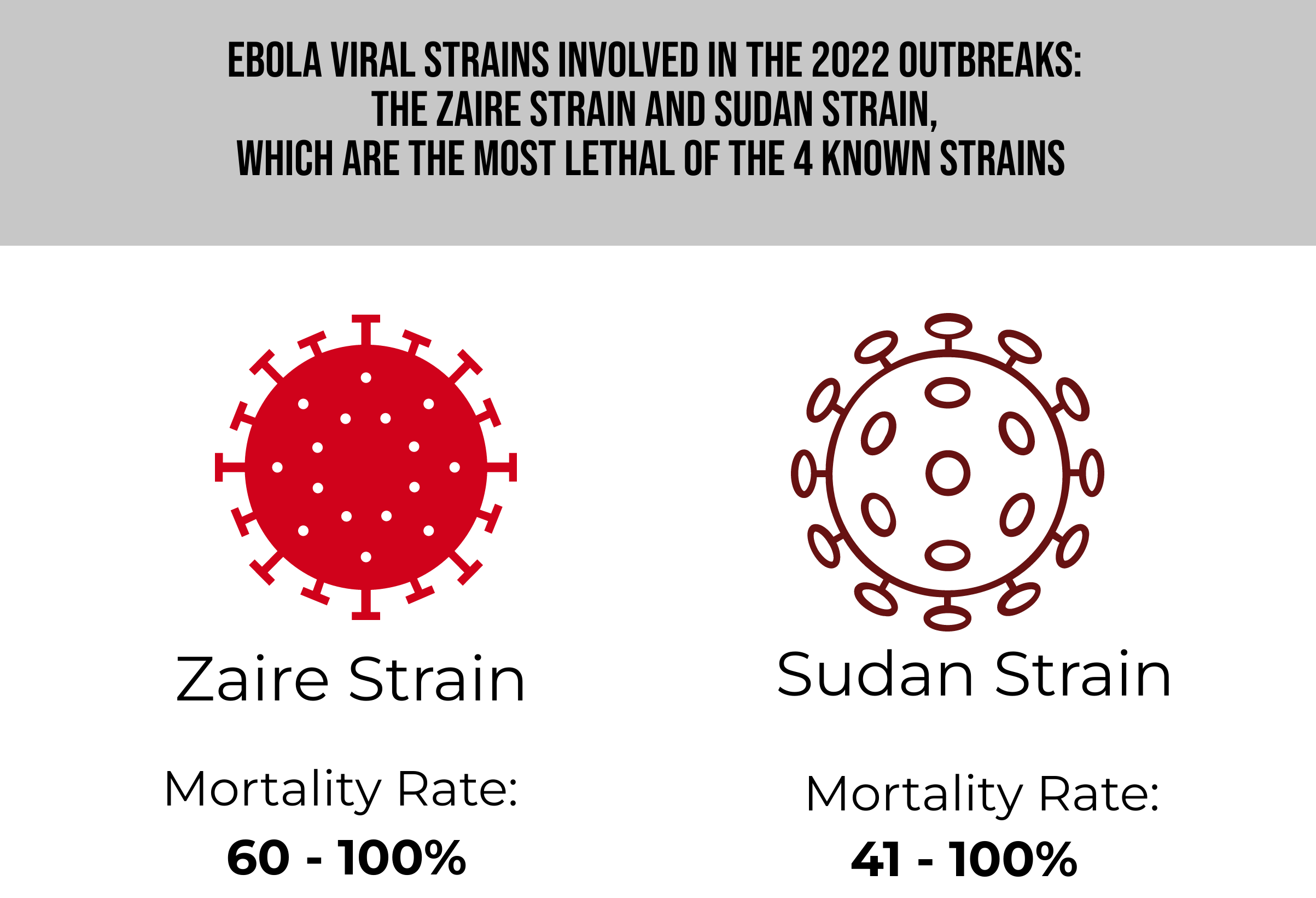

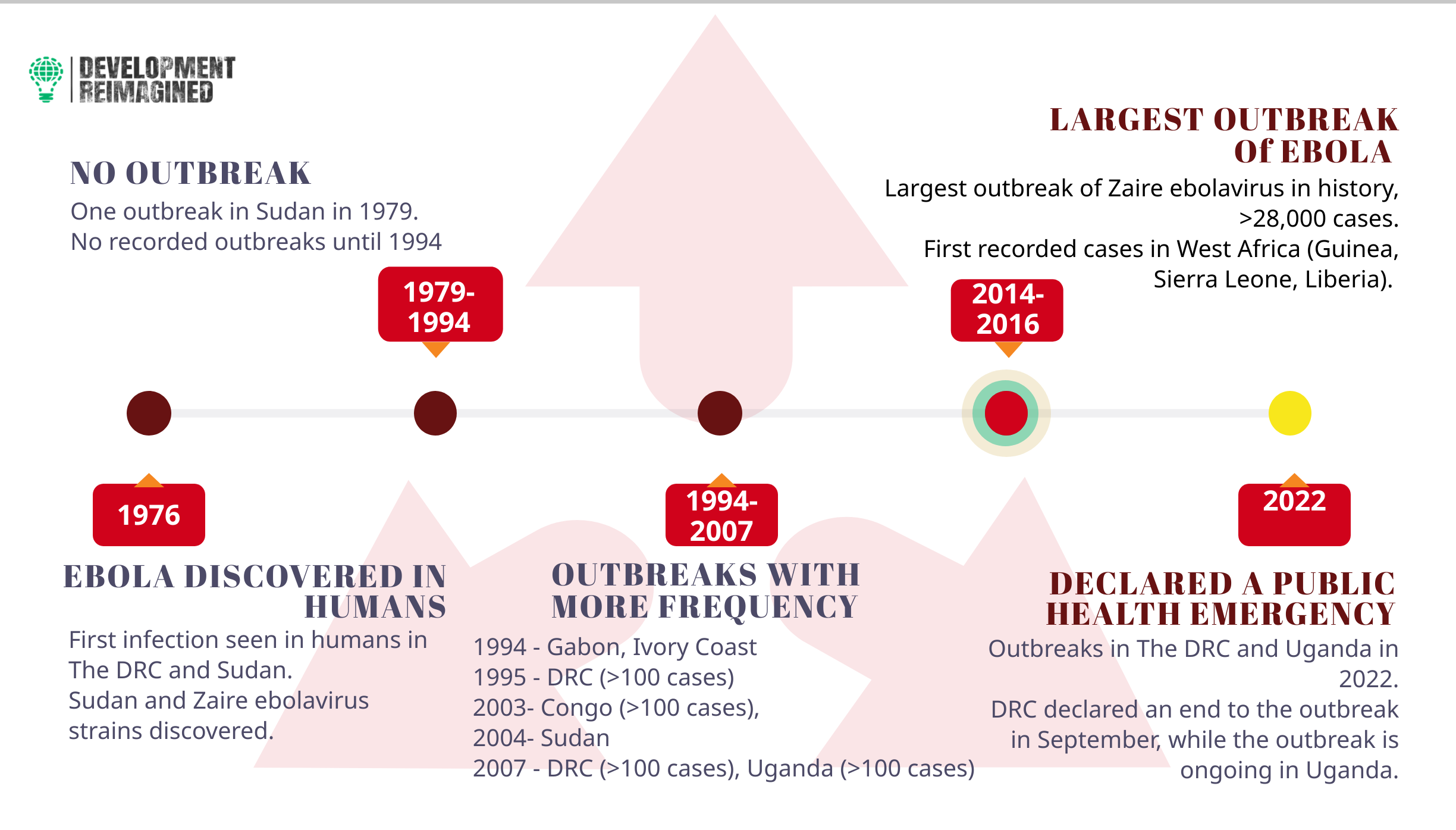

Originating in Sudan and the DRC in 1976, there have been several EBV outbreaks; between 1976 – 2008, the total case fatality rate for EVD victims has been 79%. The largest outbreak (Zaire strain) was in 2014–2016 with over 11,000 fatalities, which started in rural southeastern Guinea and within weeks had spread past land borders to Sierra Leone, Liberia, Nigeria, and Senegal, then overseas to Spain, and the US to become a global epidemic within months.

EBV is considered one of the deadliest viral diseases, with a mortality rate ranging between 53 – 88%. The disease is recurrent in central Africa and the Philippines, with a high rate of contagiousness and transmissibility, permitting rapid spread via contact with bodily fluids and/or tissues of infected animals including chimpanzees, gorillas, monkeys, antelopes, and porcupines – all commonly handled as bushmeat. Fruit bats are thought to be the main host of the disease. It then spreads through human-to-human transmission via direct physical contact with infected bodily fluids and indirectly via contact with contaminated environments.

Its initial symptoms according to the World Health Organization (WHO), include a sudden fever, intense weakness, muscle pain, headache, and a sore throat – most of which are difficult to distinguish from other common diseases like malaria, meningitis and typhoid. With subsequent stages, vomiting, diarrhea, development of rash, impaired kidney and liver function set in, then incidences of both internal and external bleeding, and the risk of death.

The incubation period lasts for 2 – 3 weeks, and from the findings of a 2020 study, diseases with longer incubation periods, such as Ebola, cause more long-distance sparking events and less predictable disease trajectories, compared to more predictable short-incubation, wave-spread patterns as seen in cholera.

These multiple factors shape EVD as a high-risk infection which should be of utmost importance for containment to the international community. The WHO recommends that 42 days from the last infection pass (double the incubation period) to declare the end of an outbreak; the countdown has begun for this as at December 2nd, when the last known patient was discharged from the hospital.

Can it be treated?

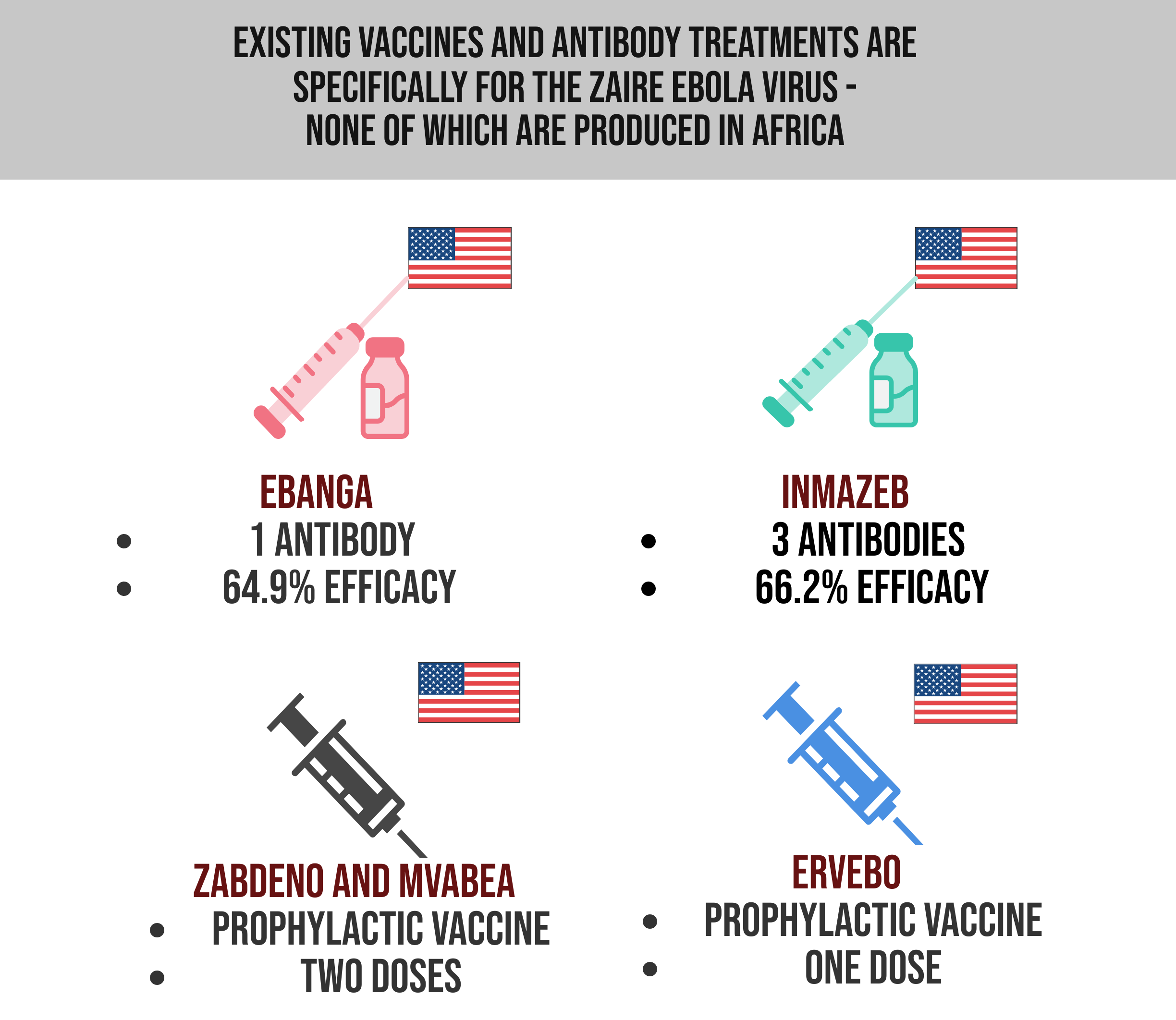

The primary treatment is supportive clinical care, in form of rehydration with oral / intravenous fluids, and is dependent on the infected individual’s immune response, but there are vaccine candidates and therapeutics for the Zaire strain, and vaccine candidates in trial for the Sudan strain.

But is this outbreak being treated with any sense of urgency?

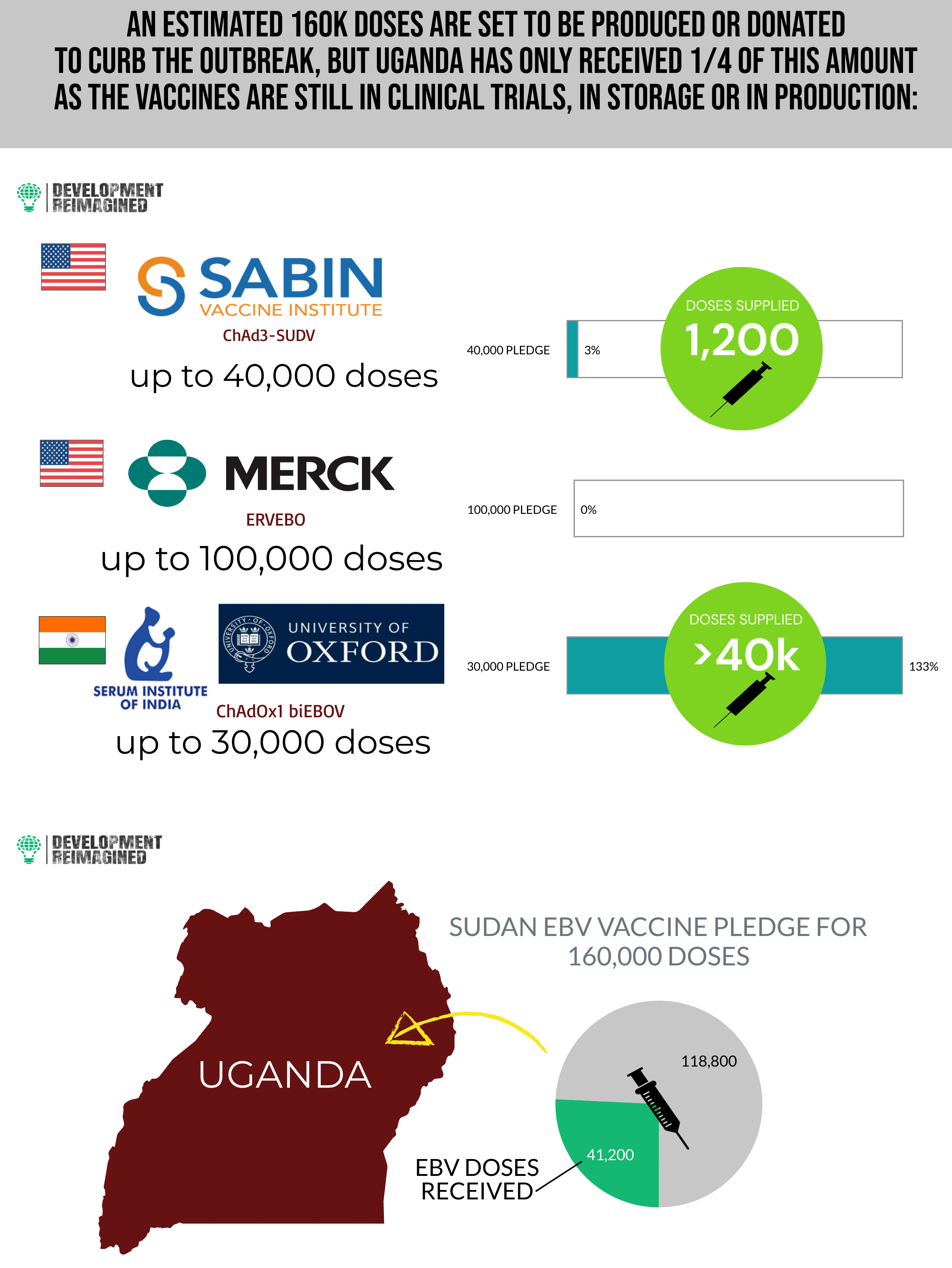

Some manufacturers of EBV vaccines have pledged to give their still-experimental vaccines free of charge to Uganda, totaling an estimated 160,000 doses to curb further transmission of the virus. The Serum Institute of India and the University of Oxford pledged to produce up to 30,000 doses by the end of November 2022 – over 40,000 of which were shipped to Uganda in mid-December, supplying an additional 10,000+ doses. The Sabin Vaccine Institute is also ahead with its candidate; the Institute promised 40,000 doses and has supplied 1,200 doses, and there are up to 100,000 doses from cold storage due to arrive from Merck.

These are commendable efforts to curb the outbreak, but local production of vaccines for EBV needs to be prioritised.

What needs to be done?

We must acknowledge the foremost of the myriad lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic; that being – “diseases do not respect man-made borders”.

It is imperative that adequate funding for local manufacturing of Ebola therapeutics lands on the decision tables, existing therapeutics supplies should be targeted at affected countries and investment into continuing research on treatments should become a priority for international organizations. The lingering risk of the infection spreading to other African states – and overseas – remains a threat, and with the supply of treatments tied to unpredictable external supply chains and overseas manufacturing, additional difficulties are placed upon affected states. Given the world’s ongoing experience with COVID, it bears stating that a disease should not need to go global to count as a priority.

December 2022