As COVID-19 spreads across the African continent, an African Union report has suggested that the outbreak could lead to a serious food security crisis in Africa, with as estimated 2.6% to 7% decline in agricultural production predicted for 2020. The FAO Director-General QU Dongyu has also issued a warning noting “quick, strategic action is needed to lessen the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food security in Africa.”

All this talk of food security has sparked debate in the Development Reimagined office- what is the best way to increase domestic agricultural production and food security across Africa? What about Chinese Agricultural Demonstration Centers (ATDCs) – do they have a role to play?

To date a number of academic studies have dived into country case studies and we’ve seen interesting articles on how individual ATDCs are operating (in Mozambique and in Malawi) but we wanted to know if this model was working continent wide and if in reality it can support food security?

So, what exactly are ATDCs?

ATDCs are agricultural centers set up by Chinese companies and institutions to transfer Chinese technology and new methods of production through demonstrations and trainings, ultimately aiming to increase agricultural productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa and thus in theory reduce food insecurity and poverty.

Why has China built these centers? Well currently, China feeds 20% of the world’s population with only 9% of the world’s arable land and a whopping 98% is made up of smallholder farms less than 2 hectares in size. The Chinese government achieved this by – alongside investing in manufacturing and both urban and rural infrastructure for economic growth – also prioritising research into agro-technology and invested significant amounts in support measures for smallholder farmers, such as packages of modern inputs including irrigation, fertilizers, pesticides and improved seeds. China wanted to support agriculture in other developing countries, and therefore at the 2006 FOCAC conference, the Chinese government pledged increased investment in Africa’s agricultural infrastructure, food security, and agricultural manufacturing sectors.

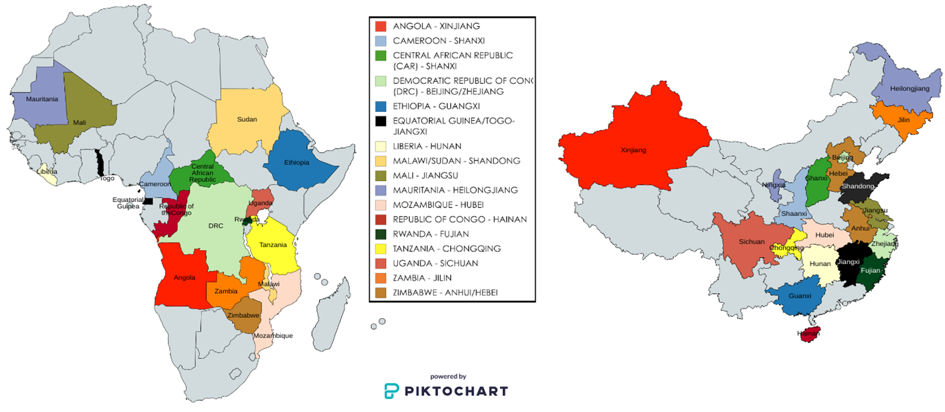

Fast forward to 2020, and at least 32 Chinese organisations (compromising 23 companies and nine educational institutions) have been operating in 24 African countries, who also typically depend on smallholder farming, just like China However, all but 7 of these countries are classified by the UN as Least Developed Nations. The interactive map below shows the distribution of these ATDCs across the continent, with particular presence in Central and Eastern Africa. Clicking on each highlighted country will provide more information.

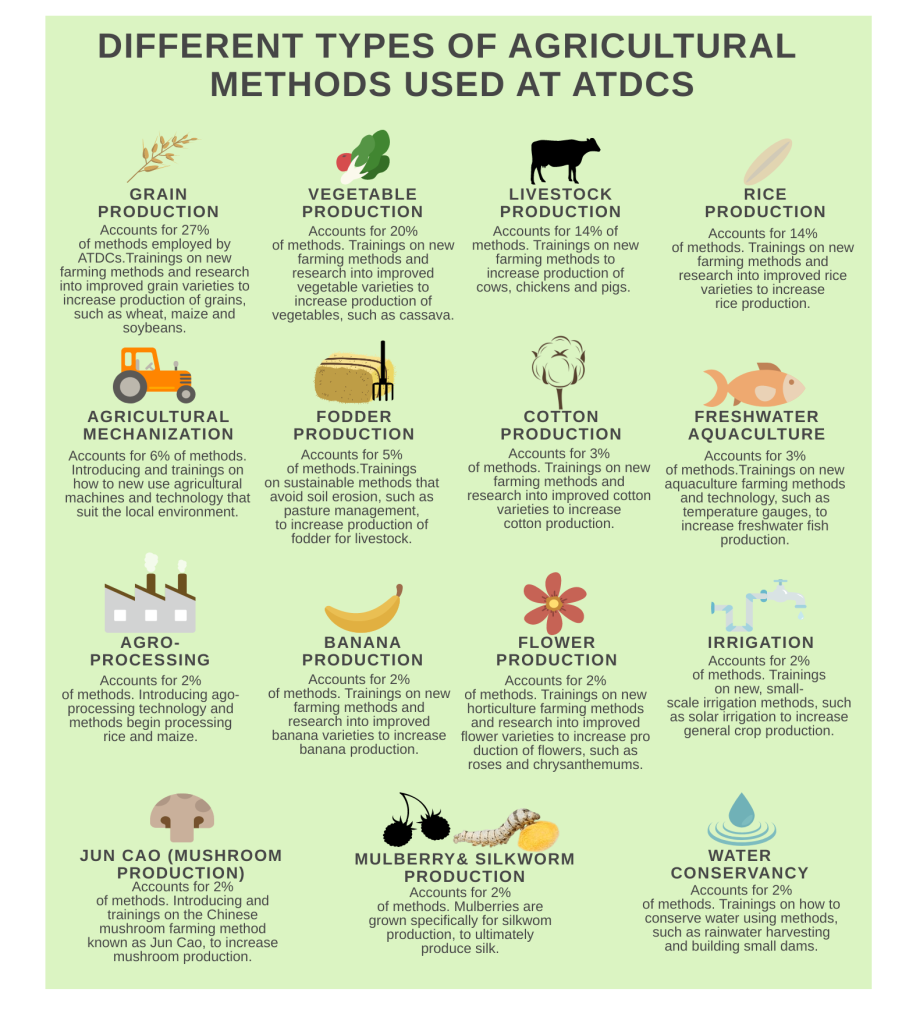

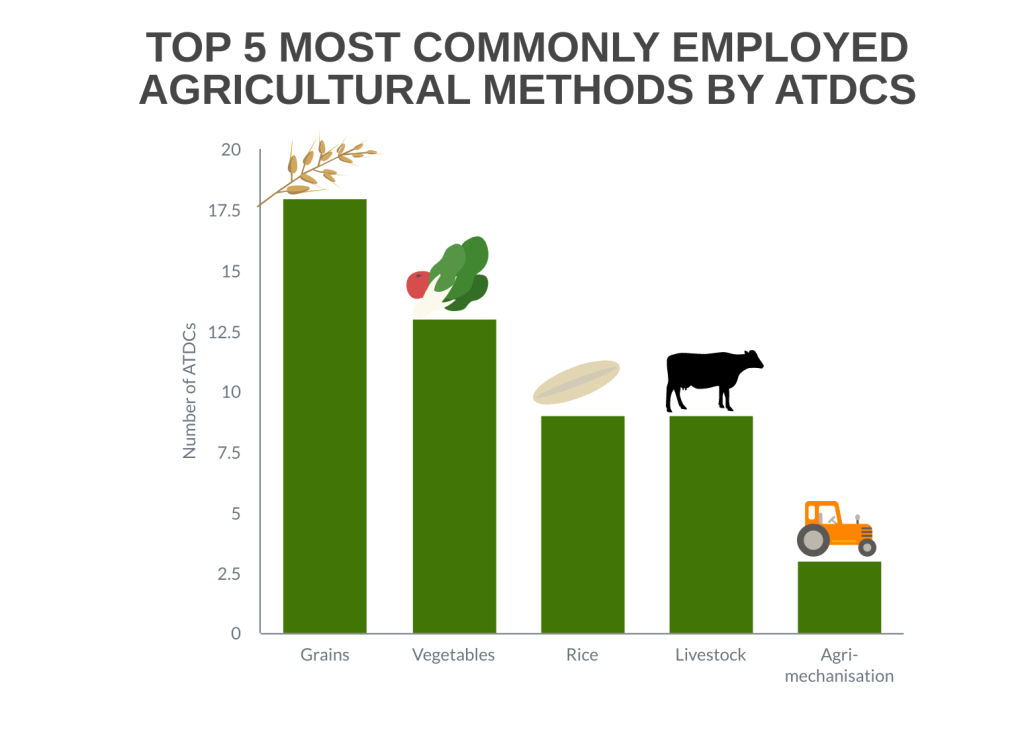

Our analysis also shows the type of agriculture varies greatly across the continent. The majority focus on grains, vegetables, and/or livestock. Some ATDCs cover a wide variety of agriculture, such as in Mozambique, the first Chinese ATDC in Africa, while others are more focused – e.g. the ATDC in South Africa is focused on aquaculture alone.

ATDCs are typically operated by the Chinese government and Chinese private sector together – in a private public partnership or a commercial-aid model – to ensure that the project is sustainable. In practical terms, this means the Chinese government gets approval from a host country to create the project (which usually means that the host country provides land for the project but keeps the land and any buildings built on it for the project as “state assets”). Then, the Chinese government puts out a tender for Chinese-Agro companies to bid for the project, with an understanding that it will fund the contractor to manage the project for the first 4-5 years, with on average, 40 million RMB or $660,000, and then hand-over responsibility to the company completely. During the 4-5 years, this means the Chinese agro-company in charge of the ATDC, must develop ways to become financially self-sustainable. This can – but does not always – require finding a local partner to work with once the project is complete.

Like some other areas of China’s international cooperation, organisations from one particular province tend to be associated with one specific African country or ATDC. As the maps below show, organisations from 20 provinces – that’s over 60% of China’s provinces, operate in ATDCs in Africa. So far, we have not found any cases of an ATDC in one country operated by organisations from several Chinese provinces.

All this sounds fairly sensible, and similar to many other donors who are now increasingly preferring to use their private sector contractors to deliver aid projects, rather than local partners or even non-governmental organisations (NGOs). China may be ahead of the donor curve in this respect (though this is not necessarily a practice evidence recommends – see further below).

But with around 14 years since ATDCs were first announced, how successful have they actually been? This was the burning question we wanted to understand.

To get to the bottom of this question was challenging. So far, we have not found a comprehensive database of the outputs and results from ATDCs. Unlike traditional ‘aid’ projects, little data exists on the outputs of ATDCs, and there are not, to our knowledge, published consistent or standard monitoring and evaluation (M&E) criteria or methods in place. However, we do know that there are internal cross-country evaluations that have been conducted by China’s Ministry of Agriculture. But it is unclear whether they have consistent, impartial and quantitative M&E assessments (that we always aim to provide as a development consultancy), or are more qualitative and subjective.

However, case studies have suggested that, generally speaking, many ATDCs were able to train and transfer knowledge of more productive agricultural methods to a large number of smallholder farmers. Some training centres also held higher-level training sessions on, for example, rice breeding techniques and field management skills for technicians and managerial methods for agricultural officials, as well as internship or study opportunities for college students.

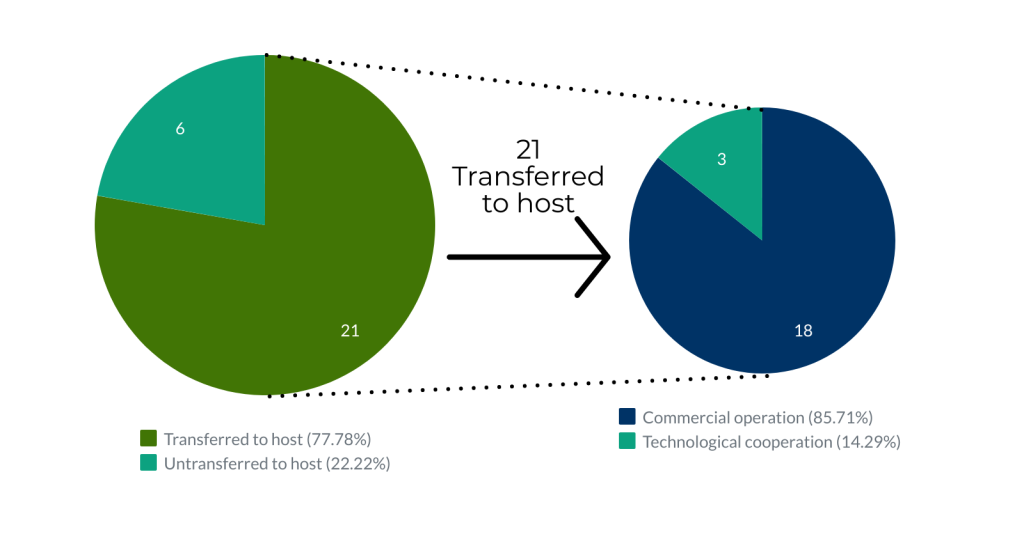

One reliable – albeit blunt – means to assess the success of ATDCs is to analyse what stage they have reached in the process of development. ATDCs that have developed beyond negotiation, feasibility, and construction, should in principle have been “transferred” to the host country.

Once this happens, they can be categorised as in one of two stages: 1, “Technical Cooperation”, a period of time in which the four aspects of agro-technology research, demonstration and extension, training, and display begin, and the centre is primarily funded by the Chinese government, and 2, “Business/Commercial Operation”, by which point an ATDC is expected to be able to establish a market-oriented, integrated agribusiness value chain, and fund itself through commercial operations.

As shown below, based on DR research*, around 22% of ATDCs have not yet been transferred to host countries, and of those that have been transferred, another 14% are not yet commercially operating. That’s an overall success rate of approximately 67%. Indeed, some ATDCs have failed. For instance, in Mali, the ATDC stopped operating completely, and the ATDC in the Central African Republic (CAR) was also temporarily suspended from operations. Our assumption (although evidence is unclear) is that both were shut due to rising in-country conflict. However, when projects are successful, they seem to be maintaining well. At least 11 of those in commercial operation have been so for five or more years, suggesting some degree of success in terms of ATDCs’ sustainability, though we do need more impartial data to conclude more.

What have been the drivers of success or failure of ATDCs?

We’ve seen from the above that the success of the ATDCs varies enormously but why?

First, recent case-study based research has suggested that the commercial element of the model often constrains ATDCs because decisions and activities become profit-driven rather than need-driven. For example, ATDCs often promote agricultural tools made by the agro-company that the smallholder African farmers cannot afford or crop varieties that do not appeal to local people’s taste. Commercial drivers also mean that Chinese ATDC staff have less time to focus on the aid element of the project, as they are highly accountable to their agro-company in China but are less accountable to the host country’s needs.

Second, there are many local factors that prevent the benefits of the ATDC project from becoming scalable and are often not considered by Chinese ATDC staff. For example, although farmers were generally able to produce bigger yields after trainings, the farmers still found it difficult to access the market in order to increase the profits they need to purchase Chinese-made agro-technology. The host country’s limited ability to support smallholder farmers with subsidies and favorable policies, such as easing the process it takes to license new seed varieties, also prevented farmers from adopting new methods and technology in the long-run. The lack of clarity surrounding the roles of stakeholders also meant that the participation of locals is limited, which makes it difficult for the Chinese agro-company to truly handover the ATDC to the host country.

So, what do the team at Development Reimagined think about ATDCs, and can they support food security?

The jury is still out. Although our infographics show the potential ATDCs have in regards to supporting growth in the agriculture sector, challenges with implementation are hindering the effectiveness of ATDCs.

What do we suggest?

Based on our experience as development experts from all around the world, we have two major initial suggestions for improvement of this model (although we would need a great deal more time and data to be able to explore this as fully as we would like to!).

First, there appears to be a problem with what development experts call the “Theory of Change” (TOC) of the project – as in how the initial project designers of ATDCs envision the result. To date, most agriculture-related programmes across Africa – whether funded by China or others – support farmers directly, like the ATDCs do. The TOC is that with better inputs (e.g. of seed, machinery, etc), farmers will increase yields and incomes. However, a challenge to this TOC is that these sorts of direct programmes do not necessarily change the return to agriculture that farmers expect. In reality, farmers do not always feel the direct and sustained benefits of the increased yields, and so their ambition falls away. This has been demonstrated by the weak outputs from many of the ATDCs, and indeed, weak outcomes of the great majority of agriculture-based projects in Africa and beyond.

At Development Reimagined we have a different TOC. Our TOC is that designing an agriculture project to increase the “value added” of agriculture (e.g. to build chocolate factories and brands rather than cocoa farms) will not only create jobs, but also create sustainable incentives for farmers to increase their productivity further down the supply chain. Such investment at the “top” of the supply chain will raise both the incomes and the ambition of African farmers, and will therefore deliver more sustained results than direct projects. We hope Chinese aid institutions (and others) can start to think about these alternative models in Africa, and experiment with them in places where ATDCs have failed.

Second, there seem to be problems of local ownership. Again, this is not unique to Chinese agriculture projects – many other donors create similar problems with the aid they design. There is no development-related reason why, for instance, a local African and Chinese agro-company could not, right from the very start, co-bid to run the project, rather than the Chinese agro-company doing so on its own. This would also incentivise the Chinese agro companies to do more research prior to bidding for these projects to ensure they really can deliver the results. It would also strengthen the input from the African-side, so that any challenges can be addressed much earlier in projects rather than at “handover” stage.

As COVID-19 brings concerns about food security back into the limelight we hope China and other key players in agriculture, will think innovatively about their agricultural aid and commercial projects around the continent to drive sustainability and growth.

*All infographics in this document were produced by the Development Reimagined Team using secondary data available online.

This article was produced by the Development Reimagined Team in Beijing. Special thanks go to Leah Lynch, Peter Grinsted, Rosie Wigmore and Wang Yu.

Published on The China Africa Project Website on May 8 2020

May 2020

References and Resources:

Goedde, L., Ooko-Ombaka, A. and Pais, G. (2019). Winning in Africa’s Agricultrual Market. New York: McKinsey & Company, pp.1-13. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/agriculture/our-insights/winning-in-africas-agricultural-market

Jiang, L. (2016), Beyond ODA: Chinese Way of Development Cooperation with Africa – The Case of Agriculture. Thesis published by the London School of Economics and Political Science. Available at: http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/3639/

Jiang, L. and Alden, C. (2019). Chinese Agricultural Demonstration Centres in Southern Africa: The New Business of Development. Research Gate, [online], pp.1-32. doi: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334363274

Kuo, L., November 17, 2016. China is on a mission to modernize African farming – and find new markets for its own companies. [online] Quartz Africa. Available at: https://qz.com/africa/788657/a-chinese-aid-project-for-rwandan-farmers-is-actually-more-of-a-gateway-for-chinese-businesses/

Mgendi, G., Shiping, Mao and Xiang, C. (2019). A Review of Agricultural Technology Transfer in Africa: Lessons from Japan and China Case Projects in Tanzania and Kenya. Sustainability. [online] Volume 11(23), pp.1-19. Doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236598

Nalwimba, N., Qi, G. and Mudimu, G. T. (2019). Towards an Understanding of Chinese Agricultural Technology Demonstration Centre(s) in Africa. European Journal of Social Sciences Studies, [online] Volume 4(2), pp.148-158. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.2858007

Rapsomanikis, G. (2015). The Economic Lives of Smallholder Farmers. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, pp.1-48. Available at: http://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/385065/

Xu, X., et al (2016). Science, Technology and the Politics of Knowledge: The Case of China’s Agricultural Technology Demonstration Centers in Africa. World Development. [online] Volume 81, pp.82-91. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.01.003