File photo, Kenyan nurse Lucy Kanyi demonstrates to media the facilities and protective equipment to be used to isolate and treat coronavirus cases, at the infectious disease unit of Kenyatta National Hospital in the capital Nairobi, Kenya. Credit: AP Photo/Patrick Ngugi, File

COVID-19, first detected in Wuhan, China late last year, has so far spread to over 166 countries, areas, and territories, infected over 207,500 people, and killed over 8,650 people. It has been declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization. The disease is not just having health effects. The virus continues to prompt travel restrictions within countries and across borders, and it has resulted in drastically reduced flows of people, services, goods, and money. Factories and companies have been closed indefinitely in mainland China, affecting the manufacturing of goods and trade between China and the rest of the world, including African countries. As a result, the world has seen oil prices plummet and stock markets tumble, and these challenges show no real sign of easing.

Before COVID-19 hit, Africa was forecast by the IMF to have six out of the world’s 10 fastest growing economies in 2020. That growth was much needed. Africa is also the continent with the largest numbers of poor people in the world – now estimated at over 400 million.

Yet it looks like the COVID-19 economic shocks could lead to a sharp increase in poverty, making it even harder for the continent to achieve the already extremely demanding UN Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. There are anecdotal reports of the economic fallout everywhere – for instance that South Africa, Nigeria, and Angola are already suffering from commodity price drops, and that Kenyan retailers are depleting stocks made in China and cannot find cheap alternatives. But how hard are these countries really being hit compared to others outside of Africa? And which countries will really be the hardest hit across Africa? To answer these questions, we have to go back to basics.

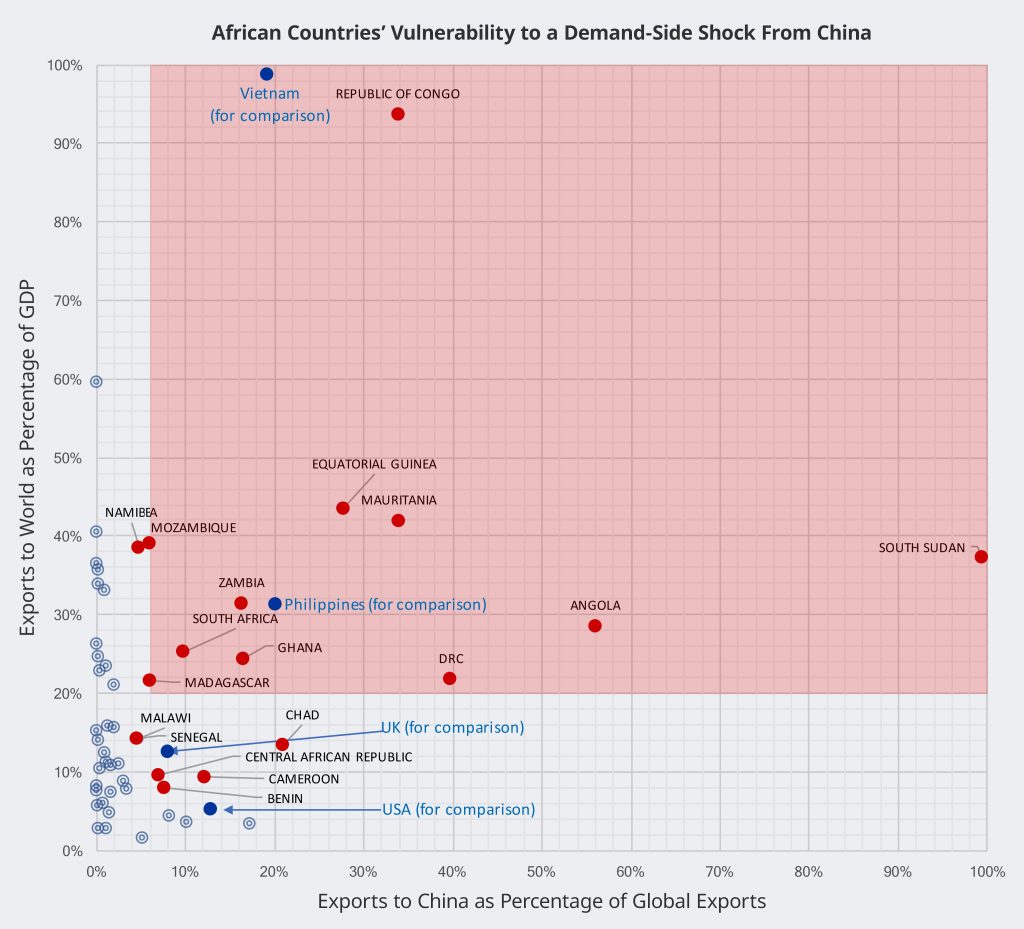

In theory, there are two types of effects that countries can feel from the COVID-19 “shocks” that have already taken place in China. The first effect is a “demand-side” shock. To explain in simple terms, we all know that several African (and other) economies export goods to China, to be used in factories or sold to Chinese consumers. For instance, Nigeria and Angola export oil to China; South Africa exports precious metals to China. But with lockdowns and other movement restrictions, as factories, restaurants, and shops closed, COVID-19 has slowed down the demand in China for manufacturing and consumer goods, and as a result, imports of such goods into China from Africa may be disrupted or prices may need to be reduced. This might, in turn, lead to production cuts and job losses in African countries.

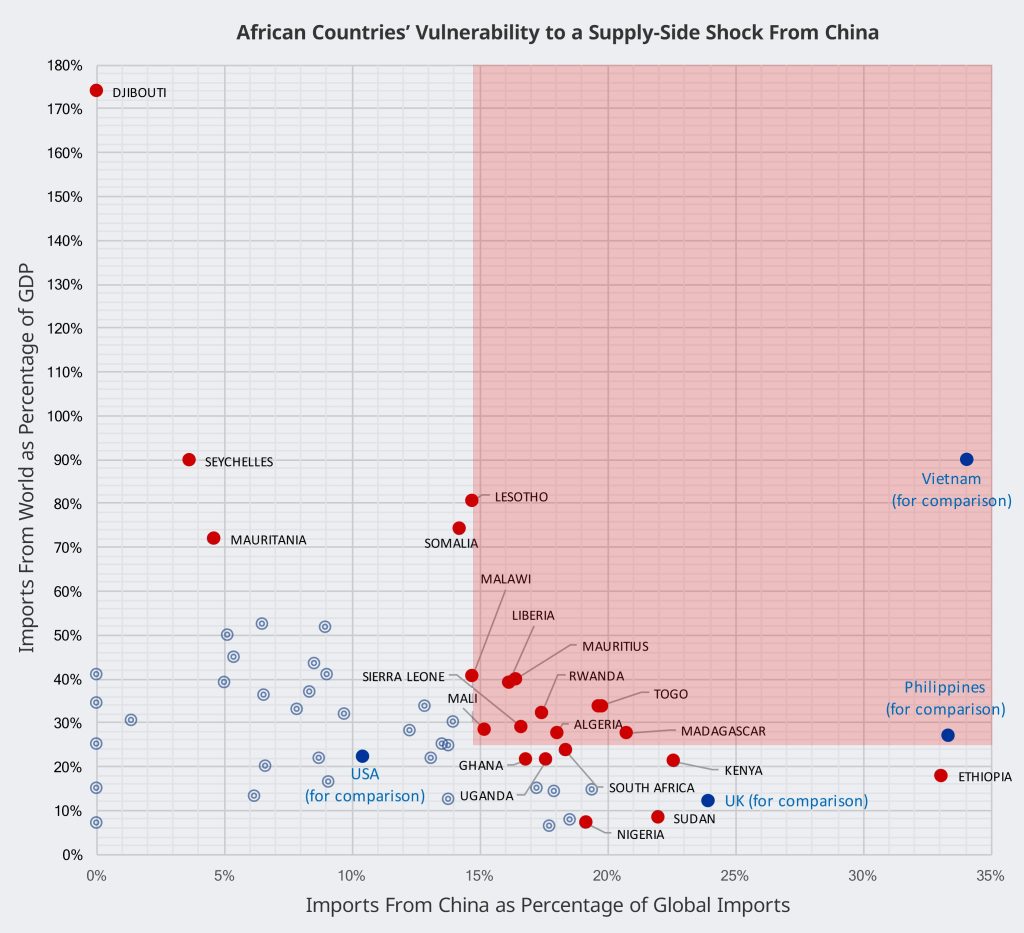

The second type of COVID-19 impact is a “supply-side” shock. Again, to explain simply, many African (and other) countries import goods that are manufactured in China for use on infrastructure projects, for sales in shops, and much more. With COVID-19, we have seen China slashing its manufacturing, in turn leading to less exports from China to African countries, and/or exports at higher prices. This affects consumer demand in African countries and can lead to the kinds of empty shelves that are being seen in Kenya.

That’s the theory, anyway. But are African economies really in what we call “danger zones” from these two types of COVID-19 shocks in China? Are they all that dependent on China? Based on analysis by our firm, Development Reimagined, and illustrated in the figures below, there is good and bad news.

First, the good news. No African country is in the “danger zone” for both types of COVID-19 economic effects. In other words, African countries will either suffer from reduced exports and commodity prices, or from stalled projects and higher bills at the supermarket and restaurants. The only possible exceptions are Ghana and Madagascar, which lie fairly close to both danger zones.

Furthermore, African countries are unlikely to suffer as much as others. For instance, Asian countries like Vietnam and Philippines, initially forecast by the IMF to grow by over 6 percent in 2020, fall in the danger zones for both types of shocks, and within each zone are worse situated than African countries. On the other hand, countries such as the United States and U.K. are very concerned about their economic vulnerability, and already have slow growth, yet they do not fall into any of the “danger zones.” So the danger zone could be somewhat larger than the cut-off points we have suggested.

But what’s the bad news? The bad news is that out of the 20 countries that do sit in the “danger zones,” 14 of these are least developed countries. That means potentially more poverty in the poorest economies.

In contrast to South Africa, and even Angola and Ghana, least developed countries such as Zambia, South Sudan, and Mauritania, which sit in the demand-side danger zone, do not have alternatives to China as a buyer nor do they have viable alternatives to their commodities for sources of growth. For instance, South Sudan was expected by the IMF to be the fastest growing country in the world in 2020, growing by 8.2 percent, but mainly because of the oil it sends to China. While guarantees for infrastructure financing as payment may reduce South Sudan’s vulnerability, there is a huge risk here, especially if Chinese buyers claim “force majeure” and renege on those guarantees. These are the most challenging cases.

Conversely, while Nigeria, Kenya, South Africa, and Ghana are often thought of as major consumers because of their rising middle classes, none actually feature in the supply-side danger zone. Why? Their economies are relatively diverse. They import from other countries as much as they do from China, and even manufacture domestically, which gives them alternative sources of income and jobs. Smaller countries such as Togo, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Mali, and Madagascar, in contrast, don’t have these alternatives. A special case is Rwanda, which also sits in the “danger zone.” It may not suffer as much as the other small economies as its significant GDP growth forecast for 2020 of 8.1 percent was expected to be based on rising domestic manufacturing and investment – this may still occur.

So what does all of this analysis mean? Should the countries “outside the danger zones” like Kenya and Nigeria stop complaining? No. The trade problems they are experiencing are real, and the UN Economic Commission for Africa has also just released analysis confirming this. However, as middle-income countries, it is a realistic proposition that their own governments can and should shoulder the responsibility of identifying the most vulnerable businesses and people within the countries and use all the domestic tools available to help avoid increases in poverty.

In contrast, many of the low-income African countries in the “danger zones” have high percentages of populations in extreme poverty – such as Madagascar with a 75 percent poverty rate. For these countries, international support from all directions – multilateral organizations such as the World Bank, the African Development Bank, high-income countries such as the G7, as well as China itself – is going to be crucial. The list of 14 least developed countries within our “danger zones” could be countries to prioritize.

But what can international partners do? Measures to assist the likes of Mozambique, Zambia, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo could include short-term collaborations with the banking sector to help large and small firms manage price falls and avoid high interest rates. For supply-side shock countries such as Liberia, Sierra Leone, and others, measures could include offering short-term loans to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and others in retail sectors to manage price increases for their imported goods and/or source more expensive alternatives from elsewhere. And for all 14 least developed countries, expanded safety nets for healthcare and income will be required to avoid individuals falling further into poverty due to job losses or health expenditures. Finally, in the long-term, as Development Reimagined has also argued elsewhere, more debt – loans – will be critical to help these vulnerable African countries diversify their economies. For instance, funds are needed to build more infrastructure and industries to locally manufacture goods – including medical products – to substitute for imports or generate new value-added exports. This is a no-brainer. It will build resilience and avoid panic in future.

Right now, we at Development Reimagined are still hoping that Africa as a region will prove relatively resilient to COVID-19 in both health and economic terms. But this is not a given, and our initial analysis suggests that effects on poverty may well be exacerbated if governments and development partners only act on the basis of media reports and singular data. Our analysis is just the start to better understanding these effects based on differences between African countries and their relationship with China. We are looking for partners to do more in-depth work to explore the dynamic effects as well as the spillovers now that COVID-19 is spreading to other regions that have a strong trade relationship with African countries. It’s urgently needed. Now is not the time to panic, but to plan ahead carefully, and for governments everywhere to act generously.

Originally published in The Diplomat on March 19th by Hannah Ryder, CEO and Angela Benefo, Research Analyst at Development Reimagined.

March 2020