Development Reimagined’s infographic series

With the second Belt and Road Forum (BRF) kicking off, all eyes are on China to understand more about the far- reaching Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the potential impacts and opportunities for developing countries. Those 124 countries who have signed BRI MOUs in particular are keen to understand more about China’s global “going out” strategy and what exactly this means in terms of financing for infrastructure and other projects.

Yet, dominating the media space is the “debt trap” narrative, accusing China of providing unsustainable loans to developing countries that are now struggling to pay them back. A widely cited case is the Hambantotaport in Sri Lanka, with the Sri Lankan Government unable to pay back their $8bn loan and therefore agreeing to a debt-for-equity swap and new Public Private Partnership (PPP) with China. Although it will generate an estimated $7bn in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) for Sri Lanka, the case nevertheless sparked worries of more countries falling into a “trap” and Chinese organisations operating national assets.

Alongside this, much of the international community is also sensitive to the prospect of BRI investments leading to debt overhang problems, having already spent close to $100bn to relieve over 35 countries of debt burdens through the Heavily Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) Initiative and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI).

To explore the accuracy of this narrative, a 2018 paper published by the Centre for Global Development assessed the debt vulnerabilities of BRI countries and found that despite the concerns BRI is “unlikely to cause a systemic debt problem in the regions of the initiative’s focus”. Positive findings – however, what happens IF countries cannot pay back – can loans be cancelled or restructured instead of turned into equity? If so, what are the best practices and lessons learnt from others?

Currently, little to no research has been published on the trends in Chinese foreign debt relief and what this means for the developing countries along the BRI. Huge discrepancies across multiple sources have made it complex to formulate a complete picture and no official records exist for both Governments or the public to refer to. As China becomes a major development partner and South-South cooperation provider, there is increasing demand for more information on China’s financial flows so that governments and development partners can build effective, efficient and results-oriented partnerships with China.

To catalyse such partnerships, Development Reimagined, in partnership with the Oxford China Africa Consultancy (OCAC), have published a number of infographics breaking down Chinese foreign debt cancellations and restructuring.

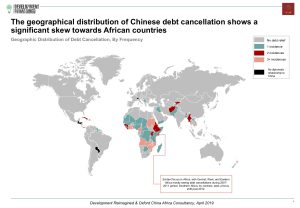

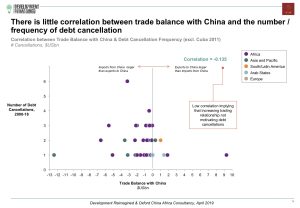

Using data from a number of sources – predominantly AidData, SIAS CARI, World Bank, IMF, and UNCTAD – we consider the relative amount, frequency, and geography of debt cancellation and provideeasy to digest diagrams to visualise the global picture of China’s debt cancellations from 2000-2018 and put them in context of other global debt relief initiatives, many of which China itself participated in, as well as changes in global aid and other trends.

Here are our top 4 findings.

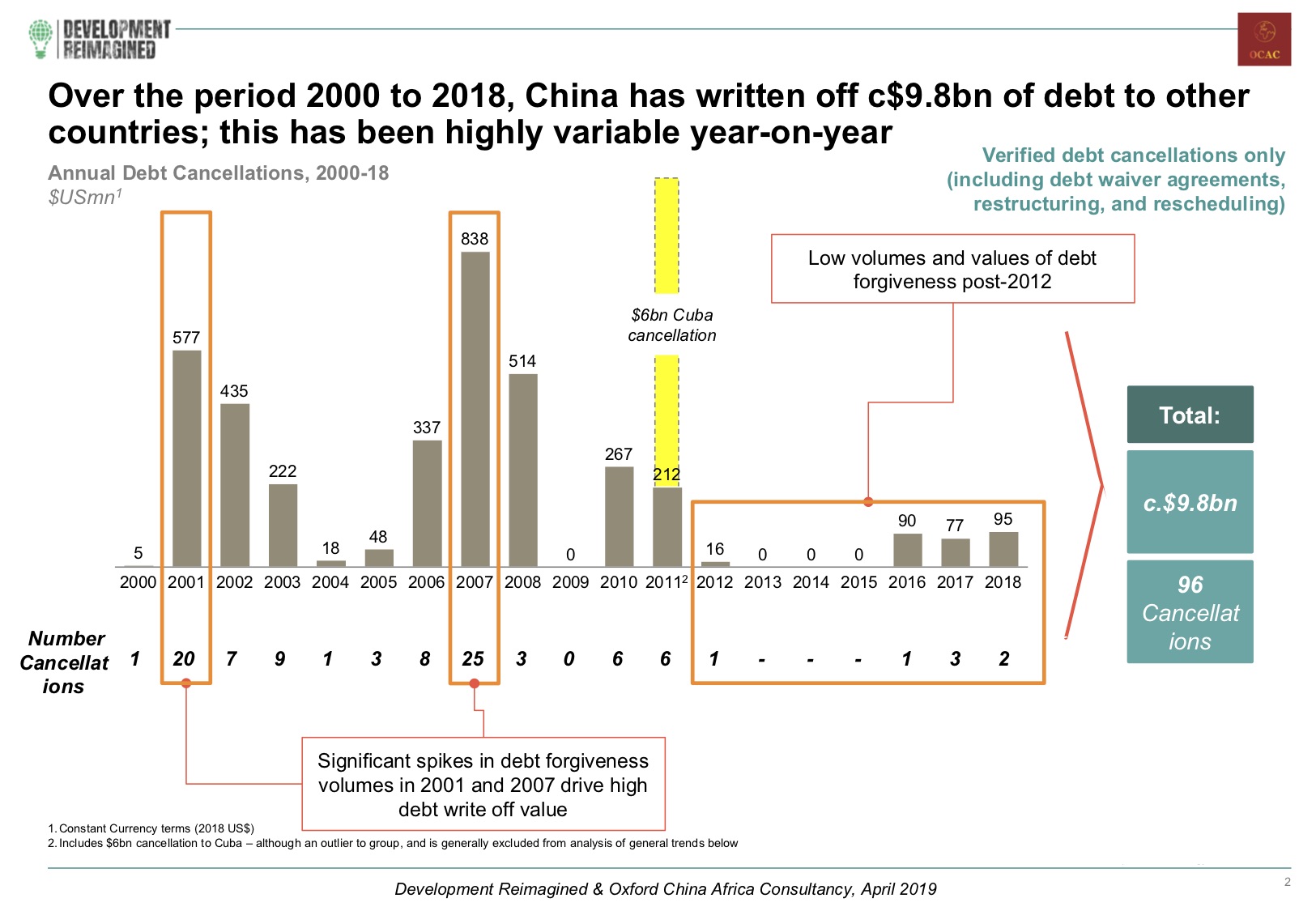

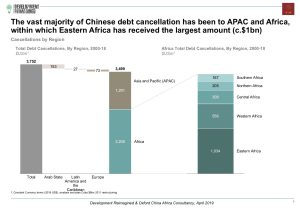

1/ Overall China has written off or restructured a total of $9.8bn worldwide between 2000-2018. This has been highly variable year on year.

In total, we recorded 96 debt cancellations or restructurings by China, including a $6bn worth restructuring for Cuba in 2011 which took place alongside and also spurred similar action by other creditors. Overall, 2007 saw the biggest spike in debt relief with 25 cancellations compared to 0 from 2013-2015. Since the BRI began in 2013 and the agreement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals in 2015, however, there have been fewer cancellations or restructurings, indicating perhaps a shift in strategy by China and/or its debtors.

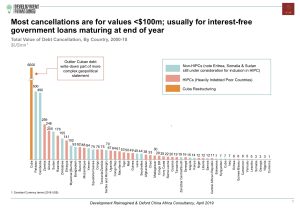

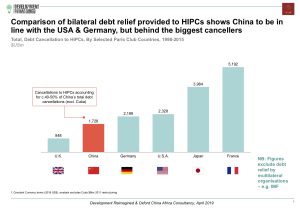

2/China has participated in the HIPC initiative as much as other creditors. But China has provided debt relief to many more countries too – across the Belt and Road, and not necessarily sticking with IMF definitions of who is/isn’t most debt distressed.

France and Japan both provided significant cancellations and further research into the impact of this can provide best practice case studies for both China and recipient countries to draw from.

Our research shows that China hasn’t only focused on least developed or (HIPC) countries when providing debt relief. This is important news for middle income countries who might be struggling with balancing debt and essential infrastructure needs. Our analysis also indicates that when looking at debt relief China doesn’t seem to look to the IMF to determine who is most in need but considers other factors. Again, this is useful and important information for struggling countries – that they can refer to other issues not just IMF analysis.

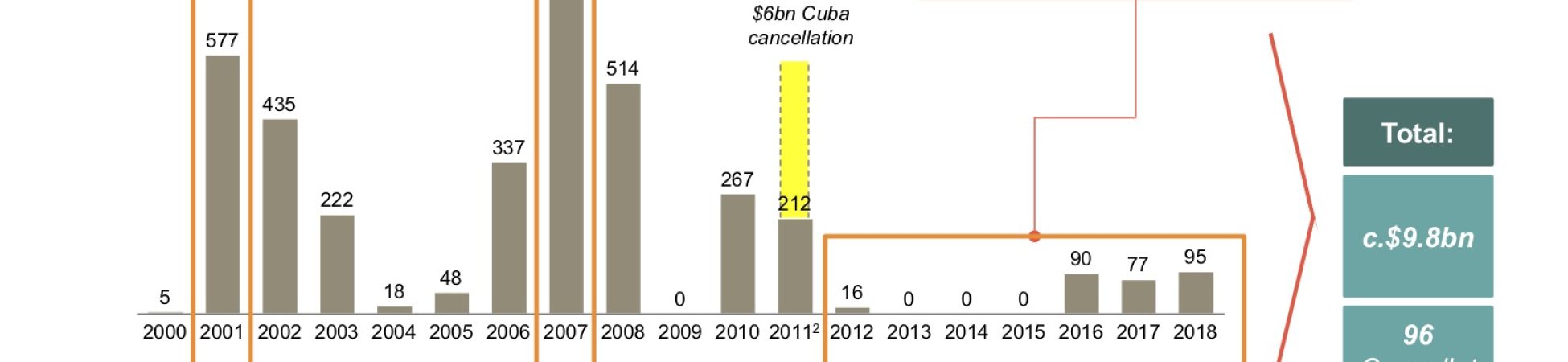

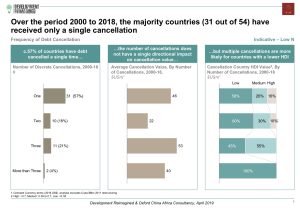

3/ Over the period 2000 to 2018, a number of countries received multiple cancellations, and some more than others. These have the most experience of negotiating debt relief with China and can provide important lessons for others.

Our results show the majority of countries have received only a single cancellation. However, countries that have received three or more cancellations are almost all in Africa, with the highest proportion in the Eastern Africa. This shows a focus on debt relief in Africa, with Central, West, and Eastern Africa, receiving the most debt cancellations during the 2007- 2011 period – the height of the HIPC initiative. Southern Africa, by contrast, has seen a focus post-2012.

Amounts also vary. In general, most countries have received cancellations less than $100m yet Pakistan ($500m) and Cambodia ($490m) have both received significant debt relief, both these countries are also strategic partners in the BRI. Zambia has received the biggest debt relief in Africa with $246m compared to Nigeria with only $3m. In some ways, Cuba is the most important case of restructuring with China to date and could share lessons with other countries.

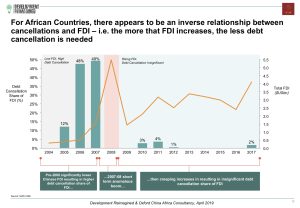

4/ There is an inverse relationship between cancellations and FDI volumes, meaning the higher the level of FDI the less likely countries are to receive debt cancellations.

Our analysis indicated that debt cancellations have declined over time, which may seem surprising in the context of overall loans from China increasing over time. Since the announcement of BRI in 2013, our results indicate only 6 cancellations up to the end of 2018.

But why might this be the case? We looked at a number of possible factors – from trade to investment, and the only factor that showed a strong influence was FDI – i.e. the more investment from China the less likely China is to restructure or cancel debt. Indeed, over time, it may be that debt for equity swaps and PPPs are being preferred and used by Chinese stakeholders rather than debt waivers, as happened in Sri Lanka. However, FDI is important in itself for meeting UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It helps create jobs, and by bringing in capital investment, technology and management knowledgeit can support social development. This is important analysis for poor countries who may want to focus on negotiating to increase their share of FDI from China to promote development, instead of relying on debt relief.

What does this mean? What recommendations do we have for China and others?

Research has shown that debt cancellations and relief have positive impacts especially in Heavily-Indebted Poor Countries. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for example, the HIPC initiative now means DRC has virtually no external arrears. The government has better financial stability and now has access to direct budget support provided by a number of development partners. Our results show that China, like many other countries, is willing to restructure and cancel debt, and we encourage Chinese stakeholders to continue to be open to these needs, because they can save lives. We also encourage other donors to explore China’s approach and see if they too can be open to cancelling or restructuring debt for countries that are not necessarily classified as HIPC countries, especially in the age of the UN SDGs, which acknowledge that poverty requires tackling even in the richest of countries.

The fact that China is willing to cancel or restructure debt is also important information for policymakers of countries in debt or that may face trouble in the future. For these countries, they can now be better aware of what is possible with China as a creditor. We recommend that they speak to and learn from others who have gone through restructurings, cancellations and debt-for-equity swaps to work out what is the best path for them, and how to negotiate the best outcomes with China. International organisations should step in to support these lesson-learning efforts.

Finally, it is worth noting what this research does NOT imply. It does not imply that countries stop taking on loans, nor that China stops providing loans. To the contrary – an ADB study asserts that in Asia alone, $26 trillion in infrastructure investments are needed over the 2016-2030 period to maintain 3 to 7 percent economic growth, eliminate poverty, and respond to climate change. However, we all need to work hard to make sure the debt goes towards productive projects, that support the economy to grow in a green manner and contribute to the UN SDGs, rather than require cancellations. Indeed, that is our role as a consultancy… We are a resource for both governments and the private sector to draw on to build connections and move forward most effectively.

Development Reimagined would like to thank the team at Oxford China Africa Consultancy, especially Brian Oosthuizen, for research and analysis.

Click to download the full analysis in ENGLISH and CHINESE

April 2019