One of the things I love about my job is getting to meet people from all over the world. Just recently, I had the opportunity to meet a bunch of officials from Saudi Arabia. They were in charge of running the Saudi Fund for Development, and they were visiting my office for something we called a “learning exchange” about development effectiveness. In other words, we wanted to understand how each of us cooperates with other countries.

Before the visit began, I was worried that the exchange would end up being me and my colleagues proselytising about what great work we’ve done. The UK is very progressive on development effectiveness – for example on transparency, or payment by results – a new strategy for which we launched last week. But I was hopeful that the Saudi’s would be able to share concrete ideas for what the UK can do better, that they had already tested out. To my delight, exactly this happened.

A little background about the Saudi Fund. It is Saudi Arabia’s official aid agency, and sits under the Ministry of Finance. It’s been operating since 1975, and since then has supported more than 500 projects in 71 countries, most of which are in Africa. It disburses about US$2 billion in soft loans annually (with repayments over 20-25 years), and it sometimes disburses humanitarian grants. For example it recently disbursed $200m for the crisis in Syria. However, despite this global operation it doesn’t have “country offices” like DFID does. It has a “borrower representative” in various countries. I’ll come back to this later.

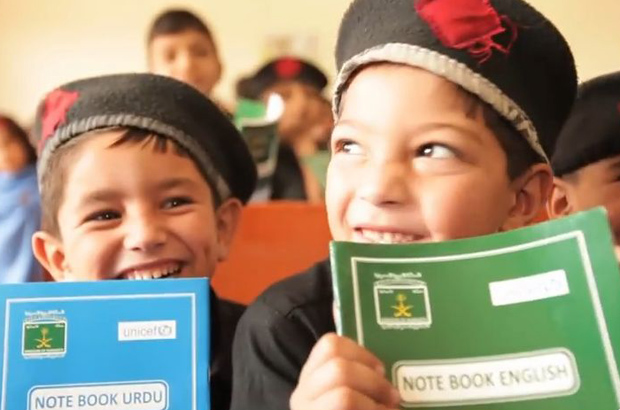

VIDEO: The Saudi Fund for Development helps girls get a better education in Pakistan

The Saudi Fund for Development helps girls get a better education in Pakistan. Picture: UNICEF

So what exactly did I learn from the Saudi Fund during their visit? Well, we began a conversation about how they make sure the country they work in really “owns” the projects, which is critical for ensuring projects have a long-term, sustained impact. It’s also important for minimising risks – which I’ve written about before.

The Saudi model was interesting. They told us they use two tools to make sure the country they are working in “owns” the projects.

First, their approval process. Every so often, their “borrower representative” speaks to the Ministry of Planning or Ministry of Finance in the recipient country to ask if they need some support. Because they are loans, most of the Saudi projects tend to deliver infrastructure – such as transport and energy. But they don’t constrain what sector they can support – that decision is left entirely to the country they are working in. However, the Saudi Fund do specify that the recipient government has to contribute a minimum of 50% to each loan, and the loan also has to be approved by the recipient country’s parliament. If a parliament is not in place the Ministry of Justice is asked to provide a “legal opinion”. These fairly operational conditions ensure the government receiving the loan is really committed to the project and that the country as a whole is in agreement.

The second way the Saudi’s try to ensure “ownership” is their procurement process, which, like the UK’s, is very open. Like us, they don’t push their own contractors or companies for the projects. However, they do take some extra measures that we don’t to bring others in. For instance, they advertise all new projects on their website and in local newspapers, both in Arabic and in English. They also, as a rule, aim not to recommend Saudi products or people when they do feasibility studies, whereas some others (though not the UK) have the opposite policy. All this means that the top suppliers for the Saudi Fund projects change regularly depending on their value for money. At the moment, their top suppliers are Chinese, French and Japanese. Once procured, sometimes the Saudi Fund pay the best supplier directly, or the recipient government pays and gets a reimbursement – again it depends completely on the recipient country preferences.

I was struck by how simple but seemingly effective these conditions and processes seemed. While the UK spends a great deal more money per year, and we deliver other forms of finance aside from loans, we are trying to simplify our rules, as mentioned in DFID’s response to a recent report from the Independent Commission on Aid Impact. In doing so, we can learn from the Saudis, and my colleagues are now following up.

For me, the Saudi visit highlighted that a genuine learning exchange has to be just that – an exchange. I hope that many more will take place between the UK and others we have not worked with much in the past, as there is lots to learn from each other. As DFID’s Secretary of State Justine Greening said when she was co-chairing the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation, “We need a new partnership with emerging nations and private investors to make sure every pound, yuan, peso or dollar spent on development has the greatest possible impact“. Learning exchanges should be a key part of that partnership.

July 2014