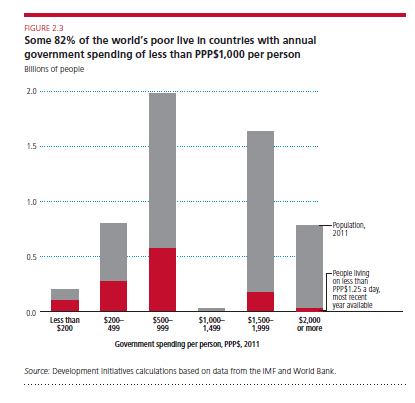

Here in the UK, according to national statistics (PDF 2.44MB) the government spends an average of £8,745 on each person per year providing services. But if you live in a lower middle-income country like Pakistan or Sudan, your government will spend around or less than £300 on you per year (NB: for the economists out there these are all at purchasing power parity rates). Just under 380 million poor people – that’s more people than the entire population of the USA – live in countries with annual government spending of less than £300 per person.

These figures come from a new report released today by Development Initiatives. Of course, such figures don’t tell the whole story, because they are “gross” figures – governments collect taxes too. And there is no consensus on what the optimal level of government spending per person is. But the figures are nevertheless interesting as they show the huge disparity and challenge of addressing poverty when there are so few resources to go around, whatever level of overall income a country has.

There are a myriad of reasons why some governments spend so little. Much of the time governments don’t raise enough taxes in the first place. The report illustrates the point that quite often countries get a lot of foreign direct investment but profits from that investment don’t remain in the country. Sometimes this is due to tax exemptions, other times due to illicit tax evasion practices, which groupings like the G8 and G20 are trying to tackle. Some other countries get very little investment or trade – often because they are land-locked or they are in conflict. There is a lot of economic analysis that looks into the reasons why countries are poor. It is in these very poor countries that often, aid – ODA – from countries such as the UK plays a strong role in relation to government spending. It can help provide governments with the money to spend directly on reducing poverty.

But this points to another issue the report raises – the amount of aid that does not reach countries – whether via governments or other locally based organisations. According to the report, Ireland, the UK and Portugal are the top three out of OECD DAC countries (a specific club of countries that try to coordinate their aid policies) that make sure most of their bilateral aid reaches countries directly. This can enable governments and other local organisations to spend directly to reduce poverty in their countries. There are some very legitimate reasons for what the report calls “non-transferred” aid, including writing off debt or or supporting the brightest and best from low or middle income countries to study in countries like the UK and apply this learning to build capacity in their own countries. But the report does helpfully raise the question of whether enough resources are reaching the poor directly in the poorest countries, and advocates continuing transparency on where aid and other resources flow so that this question can be investigated in more depth.

Many governments around the world are doing their very best to tackle the root causes of poverty in their countries. But so often they lack the resources to do so. My hope is that in the next twenty to fifty years, these countries will find themselves in the situation we find ourselves here in the UK – trying to find the right ways to minimise spending, rather than having to keep working so hard to increase it.

——————————————————————————————

Originally published 23/09/13 by Development Initiatives

September 2013