Development Reimagined’s infographic series

Trade is always changing. It’s a fact of life. According to economic theory, there will always be some countries or areas that have advantages – cost and efficiency wise – in producing certain goods over others. These countries will export more to other countries, and other countries purchase from them. And such advantages will change over time.

But it’s also a fact that trade matters to development. Some countries such as China, Korea, Thailand and UAE have created millions of jobs and cut poverty spectacularly by orienting themselves around trade.

At Development Reimagined, our clients often ask us about trade with China, an increasingly critical component of any country’s or business’ development strategy. However, China’s trade patterns exist within other global drivers and patterns. That’s why for our next series of infographics we decided to explore a data set that – to our surprise – hadn’t been analysed anywhere before… The trade patterns between Africa and some of the largest countries in the world – the G20…

This exclusive data analysis is also important in the context of the upcoming G20 Summit in Osaka, Japan from 28-29 June, and the first China-Africa Trade Expo in Changsha, China from 27-29 June. The latter represents a new zeal by China to open its borders to African products. But let’s come back to that. For now, some quick history and context about the G20….

Who are the G20 and why do they matter?

Spurred by the Asian financial crisis back in 1998, the governments of 19 countries and a region – the EU – began meeting regularly from 1999 onwards to discuss and coordinate their internal financial and economic policies, in order to have a stabilising, positive effect on the rest of the world. The 20 together account for 65% of the world’s population, 84% of the world’s economy, and 79% of the world’s carbon emissions. Over time, the G20 have begun to coordinate on other types of policy impacts on the rest of the world. For instance, since the UK Presidency in 2009, the G20 has made initial agreements on climate finance, which have been helpful for UN negotiations. The Chinese Presidency in 2016 also initiated discussion on how the G20 can directly support industrialisation in African countries.

However, to date the G20 have not collectively reviewed how their trade patterns affect Africa’s economies and development potential, and what solutions they could offer.

So – we took on this task, and these are the 5 headlines we found:

- The G20 accounts for a huge majority of trade with Africa – but that trade is tiny

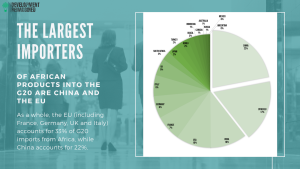

China is the largest bilateral trade partner for most Africa countries, surpassed only by the EU as a whole. China (22%) and the EU as a whole (33%) are also the largest importers of African products into the G20.

However, on average just 3% of all products imported by the G20 come from Africa.

- A few countries dominate African imports into the G20

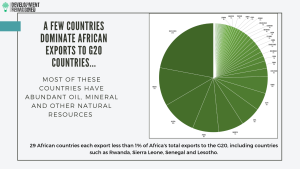

If Africa’s trade with G20 is limited, it is even more limited for the majority of African countries. There are 29 African countries that each export less than 1% of Africa’s total exports to the G20, including countries with big industrial plans such as Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Senegal and Lesotho. Even Ethiopia, known for its work since 2012 to upgrade its manufacturing and export potential, accounts for less than 2% of Africa’s exports to the G20.

In contrast, those countries that have large shares of exports to the G20 have abundant oil, mineral and other natural resources (such as Nigeria).

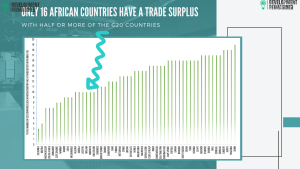

This “extractive pattern” is not reserved to China. Only 16 African countries have a trade surplus (i.e. export more to than import from) with 50% or more of the G20 countries.

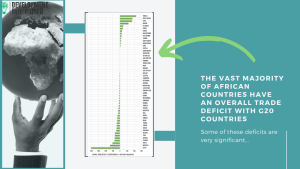

- The vast majority of African countries have an overall trade deficit with G20 countries

On average for every $1 of African exports to G20 countries, $1.4 goes back to the G20 as imports into Africa from the G20. This average masks huge differences across the G20 and for specific African countries.

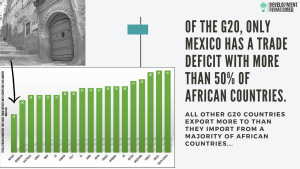

The result? Of all the G20 countries ONLY Mexico has a trade deficit (i.e. it imports more from than it exports to) with more than 50% of African countries.

- Imports from Africa into the G20 have mostly been on the rise, but from and to very low levels

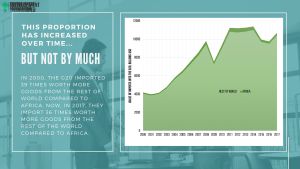

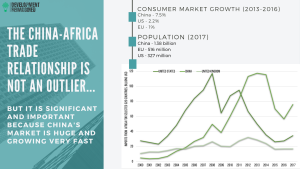

For most G20 countries, their imports from African countries have overall been growing over time, with some declines that can be associated with commodity prices due to their timing. This generally rising trend is the case for China, which is important and significant – as China’s market is huge and is growing fast. There are signs that China is diversifying its trade with African countries. However, together the G20 still import 36 times more goods from outside of Africa than from within the continent.

Interestingly, China and the US – as the two largest world economies – have moved in opposite directions since 2000, when they both imported approximately 43 times more goods from non-African sources than Africa. Now, China imports 22 times more goods from non-African sources, and the US 70 times more goods. Changes within the G20 seem uneven, and un-coordinated.

- The G20 exports proportionally more to larger, more industrialised faster-growing African countries than it imports from them OR exports to the poorer nations.

This final finding is critical – because it indicates a structural challenge. It implies that even if African countries improve internally and develop what economic theory might suggest are “comparative advantages” – e.g. in labour with its large youth population, the current trends suggest African countries may simply bring in more and more imports from the G20 and other richer nations. We are not yet seeing – and there is little evidence to suggest that we will see – the transformation of African economies from being net importers to net exporters.

Even a country like Egypt – with an abundance of high-yield and high quality agricultural goods, a strong manufacturing sector, high-tech solutions and services – imports more than it exports to G20 countries. Indeed, it has the largest absolute trade deficit of all the 55 African countries.

Is any of this really a problem?

In sharp contrast to the findings above, economic theory suggests that the future of trade should be centred in Africa, rather than G20 countries or the rest of the world. Why? Over the past 40 years, starting with economic advantages such as an abundance of cheap labour and smallholder farmers, China has taken huge steps to place itself firmly at the center of world trade, while climbing up the value chain from exporting raw agricultural and other natural resources, to exporting manufactured and increasingly high-tech goods. In 2016, China made up 13.8% of the world’s total value of exports. It used active domestic policy – such as special economic zones, combinations of direct and indirect subsidies on production, market protection (or “import substitution”) and more to get there.

But China also had the support of the rest of the world to do so. China joined the WTO in 2001, the richest countries opened up tariffs barriers, shifted production to China, and invested in China despite controversial policies such as joint venture requirements. A Mckinsey index suggests that the world’s exposure to China increased from 0.4 in 2000 to 1.2 in 2017.

China saw it’s own potential for growth and transformation. And the rest of the world did too.

The world is now increasingly talking about Africa’s growth and transformation potential. Africa has the same economic advantages that China did. Cheap labour, millions of smallholder farmers, increasingly healthy populations, and more. China’s factories should – all other things equal – begin to shift to African countries.

In addition, the 55 African countries have just come together to create the largest free trade agreement in the world. The AfCFTA as it is known is expected to unlock internal trade as well as new export routes.

Furthermore, African countries have been opening up their business environments and building industrial zones and infrastructure to attract investment. A recent UNCTAD study found over 237 industrial zones and parks across Africa now. Indeed, many G20 aid programmes are now designed to support these efforts – known as “trade facilitation” or “aid for trade” programs.

In contrast, the global policy environment for trade with African countries has hardly shifted since before the Doha trade round was initiated back in 2001. In some cases, it has worsened, with preferential trade agreements being used as political tools rather than enablers, or being disregarded through use of non-tariff barriers, both for agricultural and value-added products.

What can the G20 do?

Our exclusive analysis shows that there is no doubt that the G20 countries have the largest levers – beyond aid for trade programs – to support Africa to sustainably enter and shift up global supply chains, and eventually get a bigger piece of the trade pie. This requires looking at how the G20 can get their own houses in order.

Areas to explore include ending domestic agricultural subsidies in favour of poorer countries – the point that led to the collapse of the Doha trade round; using G20 buyers, consumer preferences and domestic incentives to shift global supply chains from China towards the African continent in a green and sustainable manner; and – recognising that Africa will now be trading as one with AfCFTA – extending current preferential trade agreements such as the US’ AGOA or the EU’s EBA to the entire African continent. These are the sorts of commitments that Japan can encourage in the G20 Summit this week, perhaps using the AfCFTA or the US-China trade war challenges as departure points.

What can individual countries and businesses, and other international organisations do? What next steps?

Our novel data and analysis above is just a first step. It can be explored in more depth, and should also be replicated for individual G20 and other richer countries as well as African and other developing country stakeholders seeking to improve or chart new trade relationships with larger players. Indeed, we believe that it’s impossible to make progress on these issues without such detailed analysis and data.

That’s why as discussions on trade here in China, at the G20, WTO, African Union and elsewhere on trade intensify, at Development Reimagined we will continue to work with all partners – at the policy level and individual business level – to provide data, case studies and practical support, to ultimately help deliver sustainable development and poverty reduction in Africa and beyond.

June 2019

.

If you are interested in exploring this data, all extracted from the UN’s COMTRADE, please let us know at media@developmentreimagined.com (a warning: it’s a large data set!).