One of the greatest aspects of being a parent is having your child question the way you look at the world. Even more so bringing up a child in Beijing, where toys, for instance, are designed with the Chinese market in mind. Last year, one toy we bought for my now 2.5-year-old son, caught my eye and has shaped my new year’s resolution for 2019, and might shape yours too.

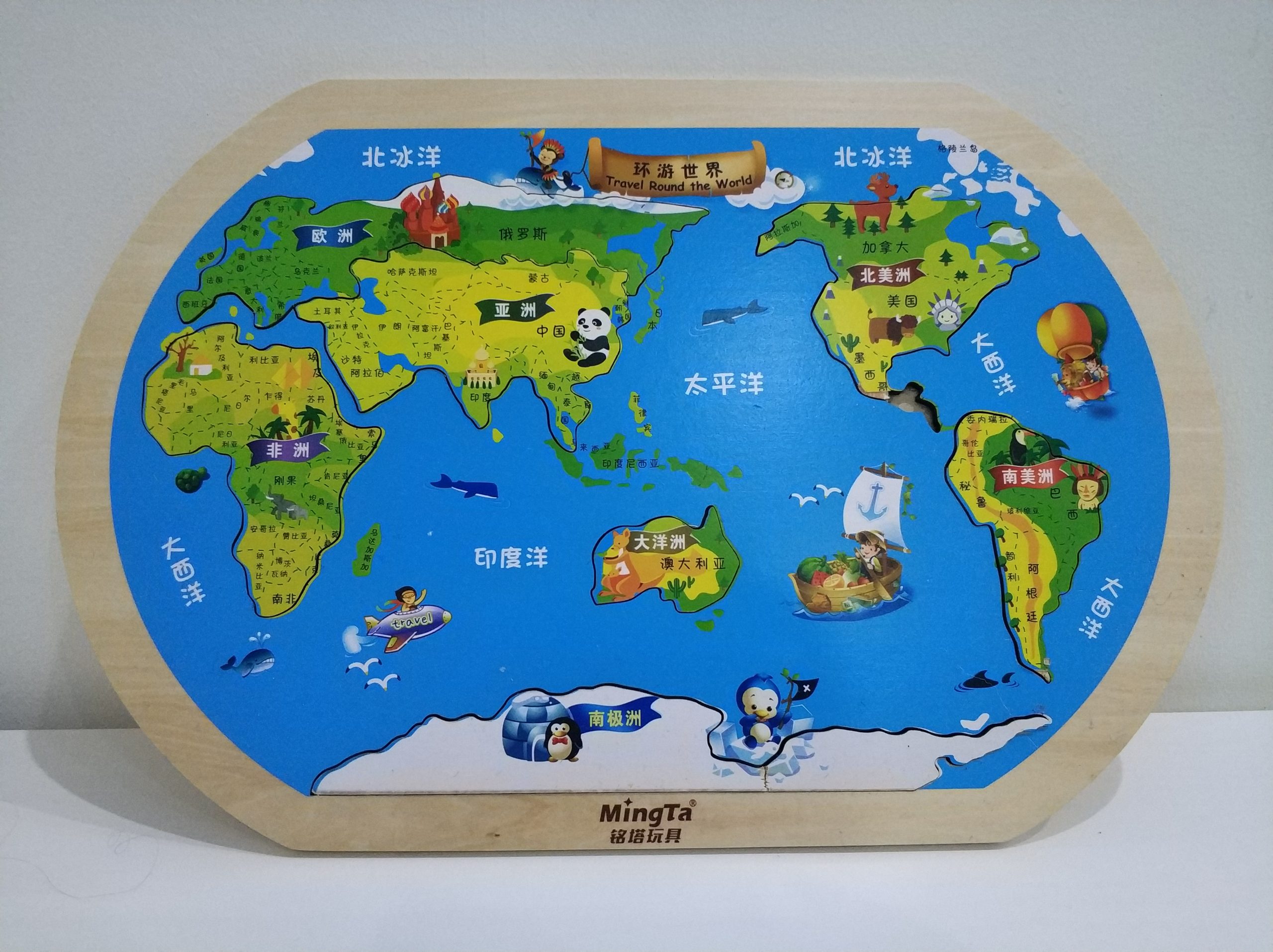

The toy was a world map, which had Australia, Indonesia, the Pacific islands and Antarctica right in the middle, showed Europe and Russia, the Middle East, Africa and much of Asia on the left-hand side, and the America’s and the Caribbean on the right-hand side. Like the Peters Map did back in 1967, which for the first time showed countries in their true size relative to each other, this map really made me think again about how we see the world.

Growing up in China, my son is being exposed to maps that show Asia, and China in particular, as not in the “East”, but actually in the “West”. Of course, this is obvious to anyone that thinks about it. The world is not flat. But we tend to look at and talk about the world as if it is flat, with certain countries on the right (the East) and others on the left (the West).

Indeed, looking at the world in this rigid way can actually meet political and economic goals. In 2018, I noticed an increasing use of the phrase “the West”, especially in articles or other media about Africa-China relations. Often, China was portrayed as a force to be reckoned with, “the West” was portrayed as a unified force against China and in some cases, against African countries. To use a format my husband shares when he lectures on writing and documentary-making – in these articles “China” and “The West” were portrayed either as the “Goodies” or “Baddies”depending on the political outlook, and African countries always the “victim”.

Franz Fanon, the distinguished psychiatrist from Martinique, once said “To speak a language is to take on a world, a culture.”I agree, and extend his point to the use of specific words. I believe the language, the words we use are important in shaping our thinking and have real consequences. That’s why, for example, I have a policy to rarely (and try to never) say “Africa”. I always say “African countries” – because Africa is not a country, and each of the 55 countries on the continent are very diverse. It’s also why I avoid saying “China does this or does that” or “China believes this or believes that”– because the country is not one actor. There are Chinese private and state-owned companies, there is the Chinese government, there are Chinese non-governmental organisations, Chinese think-tanks and academia – and like in all countries they all act and think differently.

So, my new year’s resolution is to add “the West” to my list of banned words or phrases. Why? You may ask and should you do the same? Yes, it doesn’t make sense when you look at my son’s map, but how harmful is it really?

It’s harmful because in most circumstances that the phrase is used, it tends to be setting two opposing powers against each other. This set up by its very nature negates the voice of others in the world, especially poorer, less powerful countries. Take when “the West” is used in the context of relations between China and African countries. In such cases, the view of “the West” – as some kind of amalgamation of Europe, USA, Canada and perhaps also Australia and Japan, but not Russia – is either:

- One of an on-going colonial nature – although the regions and countries I’ve just mentioned all had quite different types of engagement with slavery and colonialism in the past, and now have strongly differing policies on immigration, multilateralism and other issues;

- Some kind of counter to an emerging “China” that is itself taking on an imperial nature and being threatening through hard, soft and a new term that was used a lot in 2018 – “sharp power”.

These are interesting narratives of course, but they do not allow the space for the views of the African people and countries to come out.

Take debt, for example, which I wrote about in 2018. The African perspective on debt is diverse, but it does include the fact that African (and most other poorer) countries actually need to raise external debt from other countries or private lenders in order to climb out of poverty, tackle climate change, and meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. If these countries do not raise this debt, they will have no chance of meeting the goals. Yet, in no articles which use the words “the West” will you find any such perspective, let alone a reference to this perspective. It’s as if this perspective does not exist, or is just not important enough.

There are many, many other issues – from trade, to scholarship, to values– where this muting of a real, vital perspective and narrative takes place. Using the term “the West” is not only meaningless in its selective, ahistorical coverage, but it also disempowers African, Caribbean, South American, Asian and Pacific countries who don’t fit. It removes their agency. This is why here at Development Reimagined we work so hard to bring new thinking that is outside of these simplistic narratives to the fore.

Another one of my favourite authors, the late Edward Said, a Palestinian-American, wrote in 1994: “Just as none of us is outside or beyond geography, none of us is completely free from the struggle over geography. That struggle is complex and interesting because it is not only about soldiers and cannons but also about ideas, about forms, about images and imaginings.”

In 2019, let’s start imagining and seeing a world where poorer countries and people, including those in African countries, have a place in the world’s ever-shifting geography. There is no East, there is no West. There is just, all of us.

January 2019