When we advise Chinese companies going abroad, especially to African countries, one of the first questions they ask is: “Is the country stable?”. We in Development Reimagined know that by “stability” many companies are not necessarily referring to what other global investors might. In fact, Chinese stakeholders often see changes in the top leadership and governments as destabilising. And in some ways, for good reason. Witness the slowdowns in Kenya’s and South Africa’s economies over the last year or so, partly due to wrangles over leadership and policy uncertainty. Chinese companies strongly prefer predictable policies and rules, whatever they are. They prefer to work in countries with clear legal distinctions for their role vis-à-vis the government when delivering infrastructure projects for them; in countries with clear rules vis-à-vis labour requirements or tax payments; and in countries where the media or other players won’t lead to unpredictable change in those rules. When policies are unclear, the companies worry the return on their investments will be low.

At the same time, the concept of clear, predictable and strong “rule of law” and freedoms across a range of top-level governing institutions is often seen as key to development. It is referred to in the 16th of seventeen UN sustainable development goals(SDGs). That goal is to, now and up to 2030, “promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels”.

With the Chinese Government’s announcement to remove two-term presidential and vice-presidential limits, and thus pave the way for more high-level “stability” in future in the country, what can be said about the implications for China’s development and diplomacy?

Economists are truly divided when it comes to what specific types of governing arrangements are key to development. Some such as Acemoglu and Robinson have provided evidence that strong rules and accountability are correlated with good economic performance,a although the direction of causality is unclear (i.e. whether it is economic growth that results in strong institutions or the other way around). Others such as Paul Collier say that certain types of institutions such as elections do not necessarily reduce the potential for misuse of public power by governments. Most recently, Yuen Yuen Ang has argued that China shows development is possible even when economic development is prioritised ahead of governance reforms (and inequality).

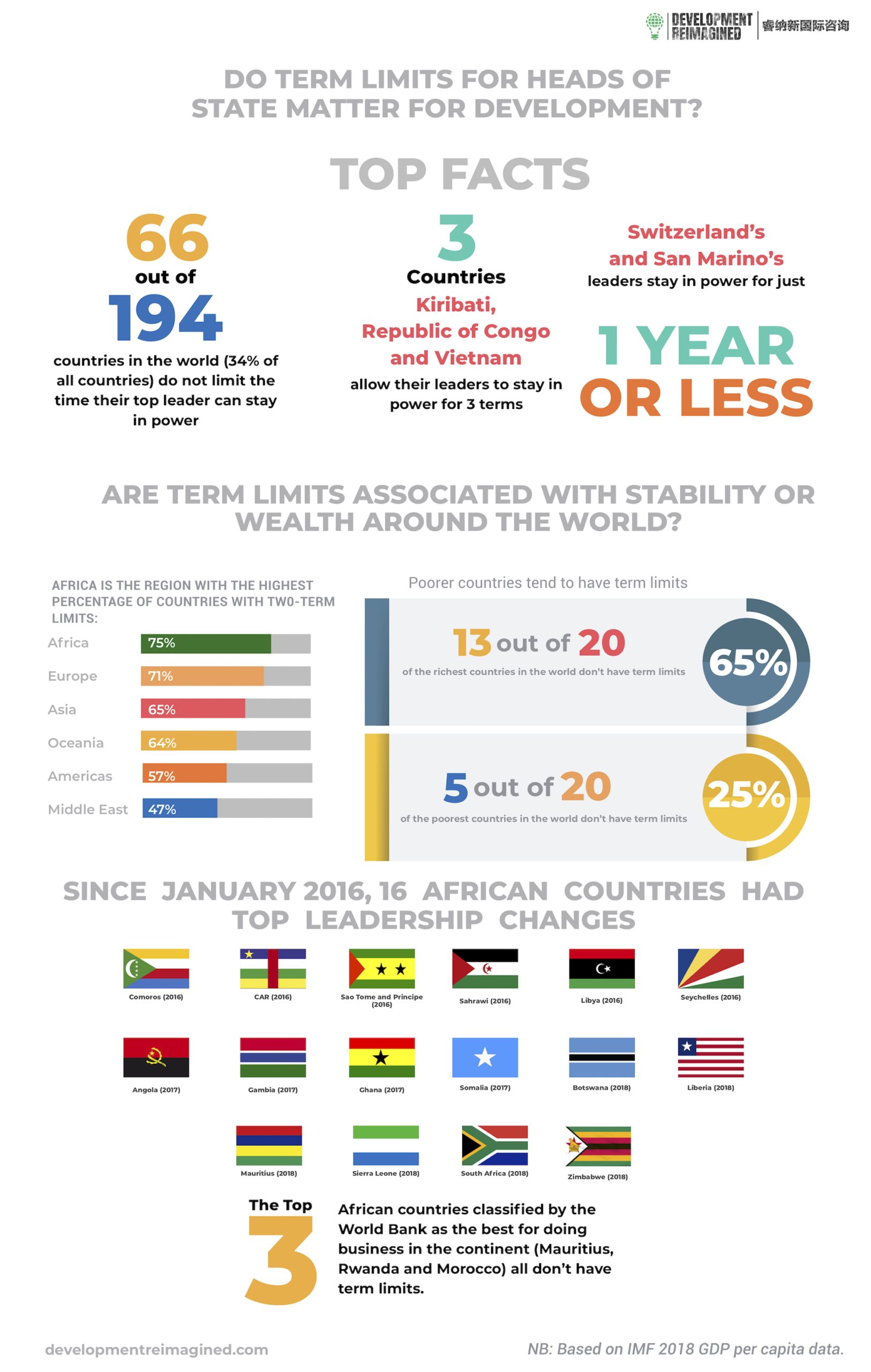

Perhaps… But trajectories cannot be guaranteed in any country. Our latest infographic shows that term limits for heads of state are a poor indicator for anything – whether its “stability” or “clear rules”.

Take some examples. Ethiopia – a country which attracts a huge amount of interest from Chinese companies and organisations – due to its so called “predictability” – is one of the 106 countries in the world that – like China in the past – has two term limits for its President, although none for its Prime Minister. Yet, its Prime Minister recently stood down because of in-country turmoil. Swiss leaders only hold one year in power, yet the country is always at the top of human development indices. On the other hand, 66 countries including economies as contrasting as Canada, Nicaragua and Lesotho all don’t have term limits. Many Caribbean countries don’t have term limits because their systems are still primarily based on that of the UK, as part of the former British Empire.

Indeed, and contrary to most perceptions, our infographic shows that it is the Middle East, not Africa, that is the region with the highest percentage of countries with no term limits in their constitutions. Hence, within the last 16 months, there were 16 changes of leadership on the African continent. Is this good, or is it bad? It’s impossible to say.

Perhaps this is why even the UN cannot be clear. SDG16 itself says little about governing institutions or specific policies, and none of the targets are related to term limits. In some cases, UN representatives have called for term limits to be imposed – for example recently in Togo. But in others, the UN has said nothing – for instance with regard to China.

Indeed, there is an argument that limits for heads of state are problematic in the complex world in which we live. In countries where there are limits, presidents are unable to see through visions for key reforms or policies to address inequality and/or their global role. Take prominent examples of Obama’s healthcare plan, or US action on climate change. Perhaps, this need for longer-term planning is a situation many countries – from China to poor countries such as Rwanda or Malawi – will increasingly find themselves in.

Right now, the jury on whether “stability” matters – especially when it comes to presidential term limits – is out. As we advise all our Chinese clients, no one country is the same, and we need to watch and analyse each carefully, matching it to what sort of predictability exactly they are looking for and need. Stable, growing markets can compensate for a lot.

And for our non-Chinese clients, at least we can now say that we expect the Belt and Road Initiative to remain a top priority for China. That may well be the only guarantee right now.

June 2018