Last week, there was a great quotation doing the rounds on Twitter, Pinterest and other social media from the Mayor of Bogota in Colombia. The quotation was “A developed country is not a place where the poor have cars. It’s where the rich use public transport”.

I think the reason people seem to like the quotation so much is that it appeared to turn usual, simple ideas of what development means “on their head”. It was similar to the effect the book Poor Economics had when it was published last year with the headline “Why would a man in Morocco who doesn’t have enough to eat buy a television?” The headline was intriguing. But once you started reading Poor Economics it made sense. The authors explained that even though nutrition is important, poor people – just like rich people – have desires and aspirations like TVs or mobile phones. It’s just that poorer people need to sacrifice more in terms of their nutrition and basic needs to meet those pressures or desires, compared to rich people. Denying the reality of people’s aspirations just isn’t realistic – and that means that poverty reduction can, surprisingly, involve TVs.

In the same way, with a bit of explanation, the sentence by the Mayor of Bogota about aiming for public transport makes a great deal of sense once you understand the importance of aspirations.

Part of the argument is to do with costs of private transport.

For example, back in 2000, the WHO estimated that 1.3 million people die around the world from traffic accidents. That’s more people than malaria kills. Such accidents are the leading cause of death for young people aged 5 to 29, 90% of which occur in developing countries. Cars also create congestion – wasting fuel and time that could be spent increasing productivity and trade. A 2011 IBM survey reported that 86% of respondents in Beijing, 70% in New Delhi and 61% in Nairobi said traffic was a key inhibitor of their work or school performance. Furthermore, 1.3 million people are killed every year from the effects of urban outdoor air pollution (the same number as deaths from indoor air pollution), with vehicles being one of the major emitters of such pollution alongside industry. Given that over half the world’s population is forecast to live in urban areas by 2020, this number is likely to keep rising. These are costs that no-one, rich or poor, aspires to. And they are one of the reasons why DFID has recently said it will allocate £1m over three years to the Global Road Safety Facility.

But, despite all these costs, I doubt that I, the Mayor of Bogota, or an institution such as the World Bank (who recently published a paper on low-carbon transport), would say that investment in roads – which will attract some degree of private car ownership – is bad. Roads are crucial, for instance to connect rural areas to markets or cities. But policy makers can still try to encourage lower-carbon, more pro-poor and safer road users such as buses or car-sharing schemes, or, in cities, encourage alternatives such as Metro and Bus Rapid Transit. Although they might be more complex, require higher upfront investment, or a particular type of contract to be viable, such alternatives could also offer opportunities for new markets around public routes – which would not exist if people used private cars. This is why, for example, DFID is helping Nigeria create a public-private partnership to build a train system in the capital city, Lagos, hopefully by 2016.

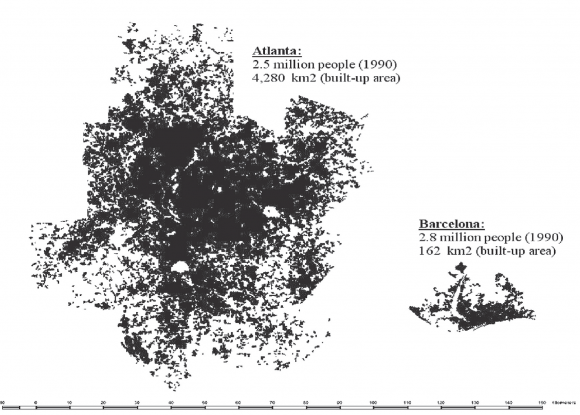

The cost argument also suggests we need to plan infrastructure carefully. In another World Bank report, there’s this great picture comparing the “sprawl” of Atlanta and Barcelona, two relatively well-off cities with a similar population:

If you were a developing country, what kinds of cities would you aspire to build?

Clearly, Atlanta has fewer options for “going green” than Barcelona will. Investment in electric vehicles alongside renewable electricity will be key for Atlanta. But if developing countries aim to build cities more like Barcelona they’ll be able to invest in and get around on public transport more easily into the long-term.

But what exactly made the Mayor of Bogota think that using public transport can really be something to aspire to? We tend to think of cars as something that people everywhere want, especially if they are rich, just like TVs. But it seems they’re not. A recent Economist article observed a declining trend in car use and ownership in rich countries. Here in the UK, people now only use their cars slightly more often than they did in the 1970s. The article suggested this could be due to a number of factors, including rising fuel costs, interconnectedness (e.g. so people can buy online rather than drive to shops), and the rise of public transport, cycle routes and car-sharing schemes.

Combined with the fact that private transport can be inequitable for the poorest people (because it requires cash up-front and expensive fuel thereafter) – these arguments made me think that Bogota’s Mayor might just be right. If the route for developed countries involves regretting not investing in public transport, it might be wise to avoid that route on the path to development full stop. Now that is something to aspire to.