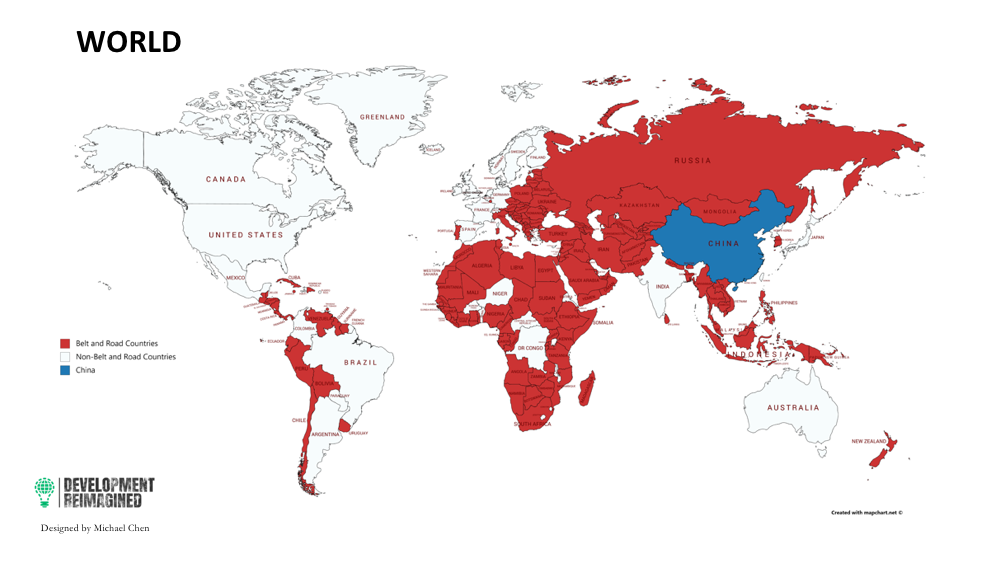

The Development Reimagined Infographic series explores which countries are and aren’t signed up to China’s flagship Belt and Road Initiative

Announced in 2013 by Chinese President Xi Jinping, The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has promised new business and development opportunities around the world, connecting regions of Asia, Europe and Africa in large investment and turnkey projects. But BRI isn’t solely about infrastructure- people to people bonds, “win-win cooperation” and cultural exchange are key elements of this initiative that is aiming to transform development across Asia and beyond.

The World Bank predicts that, if the proposed BRI projects are completed, they have the potential to increase trade along the 6 economic corridors, and maritime ‘roads’ by between 2.7% and 9.7%,increase income by up to 3.4% and help 7.6 million people lift themselves from extreme poverty[1].

But of course, the impacts in each participant country are widely varied, with equal parts optimism and scepticism for the future of BRI from multiple different stakeholders… In addition, the lack of transparency around what is “in” or “out” of the BRI makes it difficult to really assess its impact with any real credibility.

Therefore, as part of the Development Reimagined infographic series, we have produced a series of maps, outlining which countries are signed up to BRI “Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs)* to get some simple but clear insights into what this means for each region.

At a global level,the BRI spans around 140 countries, including China, involving two thirds of the world’s population[2]. Specifically, this amounts to 61.5% of the Caribbean, 66.7% of South America, 42.6% of Central America, 100% of the Middle East, 97% of Asia (excluding the Middle East), 57.1% of Oceania,72.7% of Africa, 56.8% of Europe[3].

It is interesting to note that two of the BRIC countries – India and Brazil – are not signed up, and of the G7 only one country – Italy – is signed up. This could indicate a wariness towards China’s increasing global presence and it remains to be seen whether more G7 and the remaining BRIC countries will join China’s flagship initiative.

Overall, a majority of the BRI’s investment is directed towards transport and logistics – railways and roads, which are connecting regions across the world and facilitating international trade. A study of 88 BRI countries in 2018 estimated that there is US$330bn of tracked projects in this sector, and US$266bn in the energy and utilities sector[4]. However, it is important to note that some of these projects were initiated prior to the signing of BRI MOUs, so these are likely to be overestimates.

In Southeast Asia, the countries with the largest concentration of BRI investment are Indonesia, Cambodia and Vietnam[5]. The sectors which are benefitting from this investment are predominantly railway and road construction, as well as power projects. However, BRI in ASEAN countries (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), has led to an increase of Chinese imports into South East Asia, particularly construction services and related financial services, which risk tilting the balance of trade significantly in Chinas favour. The key to retaining a balance of trade, which benefits both China and ASEAN countries, is promoting investments that promote value-added industry in these areas to boost the exports of the recipient country.

It is particularly interesting that 100% of the countries in the Middle East are interested in the BRI. The region is strategically important as a crossroads connecting East with West, but it has challenging politics and security. Nevertheless, China has pledged to provide $35 billion in financing and loans[7]to Iran and plans to construct a railway connecting Tehran and Mashhad. Furthermore, China has also recently completed a high-speed railway in Saudi Arabia[8]. China’s involvement in and relationship with both of these countries through the BRI is fascinating in itself and there are varying expert views on which is most crucial[9]. Over the next year, it will be interesting to see how China can manage such tensions, whilst continuing to invest through the BRI in the region.

In central Asia, the BRI initiative is providing the opportunity for landlocked countries, such as Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, to increase their trade with China. For instance, the New Eurasia Land Bridge Economic Corridor connecting China with Europe via Kazakhstan and The China-Central Asia-West Corridor which links China’s Xinjiang province with Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. The economic motivation of proposed BRI investment in this region is to bolster support from the continent as well as to open future trade routes by constructing infrastructure servicing the link between China and Europe.

In Africa, initial BRI signatories were concentrated in East Africa but have recently extended to cover 40 out of the 55 countries. Hence, to date, a railway connecting Ethiopia and Djibouti, and an internal railway in Kenya have been constructed using Chinese financing from financial institutions such as EximBank (who funded 90% of the Kenyan project[6]) and China Merchant Holdings Ltd, with plans to potentially extend this line into Uganda and Rwanda. If the BRI fulfils its promise to provide the required infrastructure and transport links, the opportunity for Chinese factories to outsource their labour-intensive branches to African countries will follow. This could result in the development of African exports to US, Europe, and even China of higher value-added manufactured goods, rather than commodities.

BRI’s engagement with Europe, particularly with Italy and Switzerland in summer of 2019, brought new leases of legitimacy to the initiative, as well as demonstrated China’s willingness to adjust its approach to the BRI. The motives of Italy’s engagement – as a G7 Member – in BRI, are both economic and political. The MOU signed by Italy had some specific and different paragraphs to standard MOUs, while constituting a step away from Brussels and the EU in Italy’s foreign policy[10]. Then, when Switzerland signed its bespoke MOU, focused exclusively on “triangular cooperation” or “third party market cooperation” in the Chinese translation, it demonstrated that the BRI is not simply a development initiative but has the potential to build Chinese and other countries’ influence around the world together.

Finally, the Latin America and Caribbean region has made a recent and significant addition to the BRI, despite the geographical distance from the original “Silk Road”. China is particularly focused on including Chile and Panama, as the two countries can facilitate the transport of Chinese goods through the Panama Canal, and their proximity to both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. One of the major BRI projects in this region is the laying of 20,000 to 24,000 kilometres of subsea fibreoptic cable to connect Chile and China[11]. This immense project demonstrates China’s motivation to use Chile as a gateway into Latin America. At a time of strained US-China economic relations, China’s growing partnership with America’s neighbours will be an area to watch.

Final thoughts…

For all countries along the BRI it is important that the infrastructure built in partnership with China draws wider foreign investment to ensure that their trade with China remains mutually beneficial. A lack of established value-added exports has the potential to make many countries vulnerable to diminishing terms of trade with China and others, and unmanageable debts from BRI projects. The infrastructure must also be green – built to the highest environmental standards and leapfrogging fossil-fuel based economic growth.

At Development Reimagined, we constantly work with different partners to support the sustainable development of the BRI, both through our bespoke advice but also through the implementation of green projects across many developing countries. Our research has deep dived into the wider context of BRI, such as this piece published on the distribution of Confucius Institutes and people to people bonds, this speech on creating jobs along the BRI and this analysis of debt cancellations along the BRI.

For more information about how DR can support you with your BRI vision contact us at: clients@developmentreimagined.com

September 2019

*maps and data are correct as of September 2019

References:

[1]https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/regional-integration/brief/belt-and-road-initiative

[2]https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/info/iList.jsp?cat_id=10076&cur_page=5

[3]Own calculations based on official BRI membership data. Country lists based on UN list of recognised countries.

[4]http://www.lse.ac.uk/ideas/Assets/Documents/reports/LSE-IDEAS-China-SEA-BRI.pdf

[5]http://www.lse.ac.uk/ideas/Assets/Documents/reports/LSE-IDEAS-China-SEA-BRI.pdf

[6]http://www.reuters.com/article/us-kenya-railways-idUSKBN18R2TR

[7]http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201901/25/WS5c4aa81da3106c65c34e6912.html

[8]https://www.beltroad-initiative.com/projects/

[9]https://thediplomat.com/2018/07/chinas-bri-bet-in-the-middle-east/

[10]https://thediplomat.com/2019/04/china-italy-relations-the-bri-effect/

[11]https://www.beltandroad.news/2019/02/17/the-bri-and-latin-america/